Currently the asbestos – which is mixed with building rubble and other materials – is being stored in sealed bags in rusting shipping containers.

Sound insulation infill

Thermal insulation lagging

Felts, blankets, mattresses, tape, rope

Asbestos boards

Gaskets, washers, drive belts, conveyor belts

Roofing sheets and slates

Drain and flue pipes

Fascia boards, bath panels, ceiling tiles, toilet seats, cisterns

Damp proof courses, PVC panels and cladding

Lab bench tops, extraction hoods, fume cupboards

Brakes and clutches

Transport Minister Eddie Noel has been working with the Planning Department to apply for a special exemption from the UK’s Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

The final decision is due to made by the end of this month.

The existence of 217 containers full of the potentially hazardous asbestos at La Collette was revealed by the JEP in 2012.

Since then States departments have encountered numerous delays in dealing with the waste and it has remained at the site.

Now Transport Minister Eddie Noel has said that a solution could be in sight – if the relevant permission is given by the UK authorities.

All the necessary paperwork has now been completed by the Jersey authorities and a decision is expected soon.

‘We have a reasonably good case, but we need to wait and see,’ he said. ‘If the derogation comes through, we are looking to start as soon as possible.

‘It will be similar to the backlog of fly ash at La Collette, which has been removed quite quickly and should be finished by April.’

The minister said it was likely that the asbestos would be buried in disused mines once it reached the UK.

Asked what the costs might be, he said that it was not possible to give an estimate or to say how much the States had budgeted for the disposal operation.

If the UK is willing to allow the shipment of the material, the work will require specialist contractors and will be put out to tender.

‘If we cannot get the appropriate authorities to give permission, we will be reverting to our back-up plan of burying the backlog of waste in the concrete-lined pits at La Collette,’ the minister said.

In any case, he added, asbestos removed from buildings in the future would not be covered by the special one-off exemption and would need to be buried in the Island.

In the the States last week Deputy Jackie Hilton asked Deputy Noel if he intended to speed up the removal of asbestos from school buildings.

However, the minister declined to respond because he was answering questions specifically about the Transport Department, whereas school buildings are the responsibility of Jersey Property Holdings, for which he also has responsibility but as an Assistant Minister for the Treasury Department.

Asbestos is a material which was widely used in the Island up until 2000. Although since banned from import or export, it is known to be present in all kinds of buildings. But just how dangerous is this substance, and what should we do if we come across it?

What exactly is asbestos?

Asbestos minerals have been in use since Roman times and are found in several global areas, including Canada, Australia, Russia, China and Brazil. During the Industrial Revolution the substance was widely mined, but it wasn’t until 1924 that the first case of asbestosis was identified in Britain.

Health and Safety director Tammy Fage said: ‘In its heyday it was a remarkable product, particularly for insulation and fire resistance. Unfortunately, no one realised that it was a carcinogen.’

Three main types have been used by the construction industry: chrysotile (white), amosite (brown) and crocidolite (blue).

‘All three are dangerous,’ said Mrs Fage, explaining that the risk is greater from materials in which the fibres are not densely packed together, or in technical terms ‘friable’.

‘Loose installation, like pipe lagging, is the most dangerous. Insulation board, which is soft and easy to snap, is intermediate but still high risk. Then there are materials such as well-bound cement, roof sheets, downpipes, vinyl floor tiles, rubberoid roofing. Often, you can’t tell by looking that it is asbestos.’

What is the risk?

According to Health and Safety, the danger arises if the material is damaged, because then the fibres become airborne and can be inhaled. Any dust released during handling will contain asbestos fibres.

‘We don’t want to be scaremongering,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘If the asbestos is intact and in good condition, it is not a problem.’

However, the statistics are not encouraging. In the UK, asbestos is the biggest occupation-related killer, responsible for more than 5,000 deaths annually. Considering that in 2012 there were 1,754 deaths on UK roads, the risk is clearly not insignificant.

Workers who may be in greatest danger nowadays are construction workers dealing with demolition or refurbishments – carpenters, plumbers, electricians and cable layers, whereas in the 1970s, 80s and 90s cases were more likely to involve shipbuilders, miners and even women making gasmasks during the Second World War.

‘The problem is that whereas road accidents are visible and obvious, respiratory disease can take from 15 to 40 years to develop – and then it is too late,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘The more exposure, the higher the risk. If you are a smoker, you are 20 times more likely to be affected.’

There is no known cure. In the UK, there is a mandatory requirement to report asbestos-related disease, and if someone can show that their ill-health is a direct result of their working situation, there is an industrial injuries compensation scheme.

In Jersey, it appears that there is no requirement to report such cases, and the recourse for individuals is through employers’ liability insurance, but only if they can show a clear link.

Of the cases brought to court in Jersey over the past five years under Health and Safety Legislation …

- 25 were accidents or incidents

- 31 duty holders were prosecuted

- 18 were related to construction

- 6 were related to building refurbishments

Where can asbestos be found?

The answer is in most buildings all around the Island, including older properties. A prime example is the former holiday camp at Plémont.

Health and Safety say they have no evidence to suggest that shiploads of asbestos were imported into Jersey after it had been banned in the UK – although there is a widespread belief that this is the case. However, Mrs Fage said that there was no doubt that a lot of the material was imported over a period of time.

‘If the premises were built before 2000, assume that asbestos is there,’ she said. ‘There is still a lot around in States buildings, schools, hotels and private households, often in garage ceilings or behind chimneys.

Last year there were 102 separate notifications by licensed contractors to remove asbestos from properties in the Island, which is some indication of the scale of the problem.

‘Anyone who works in construction should have awareness training so that they know exactly what asbestos is, where to find it, what to do if they suspect it or if it has been disturbed.’

What does the law say?

Every workplace building should have an asbestos management plan and a management survey. If construction work is undertaken, a demolition / refurbishment survey is required to make sure that asbestos is identified and dealt with in advance.

Most importantly, says Mrs Fage, contractors must ask for the survey. ‘The first prosecution we carried out years ago was a major Island hotel. They had a survey, but the contractor did not think to ask and the hotel did not pass it on. A similar thing happened on States premises, and both the States and the contractor were fined.’

Of the six cases involving asbestos brought to court over the past five years, all have occurred inadvertently during refurbishment work, and in all cases the contractors failed to ensure that a survey had been carried out before starting work.

‘We find it frustrating and disappointing that we keep having to prosecute, but it is difficult to know what else we can do,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘The industry has to take it on board.’

The level of fine is unlimited, but for any business the publicity associated with the court case is more damaging.

How should asbestos be disposed of?

Health and Safety make a clear distinction between the legal requirements, depending on the type of asbestos.

The ‘friable’, most dangerous forms can only be removed by a contractor licensed by the Social Security Minister. The department must be notified of the work 14 days in advance, and Health and Safety review every notification.

For denser material, such as asbestos cement, a license is not required provided the contractor has the approved level of training.

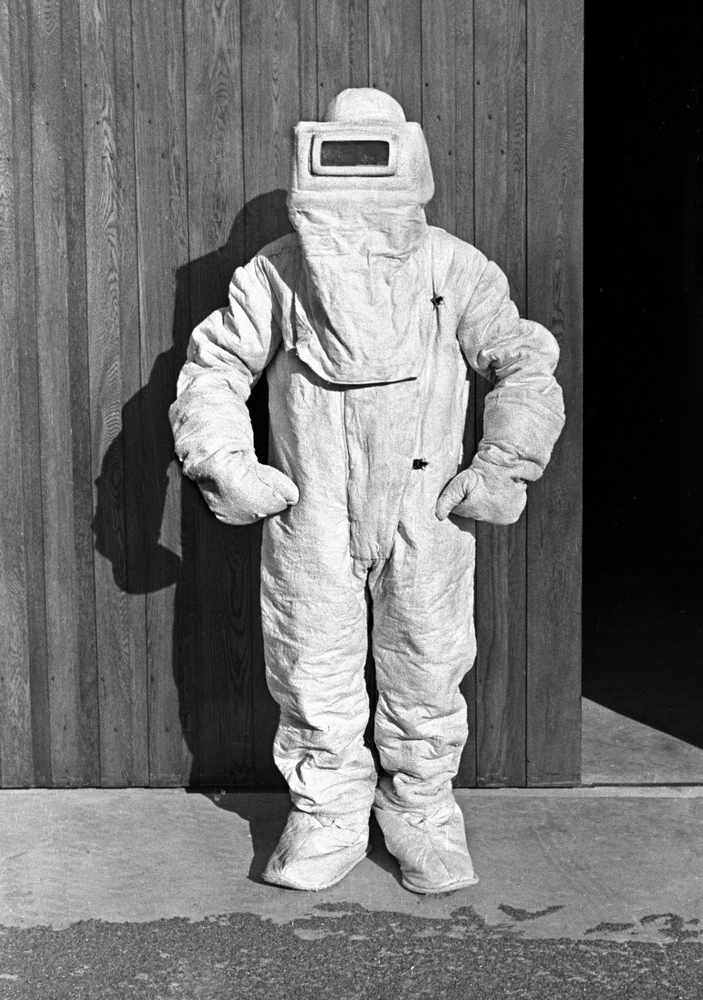

For the average householder wanting to renovate their home, the discovery and disposal of asbestos can be an expensive and time-consuming business, involving safety suits and pressured tents to keep any fibres in. ‘There is no safe level of exposure,’ said Mrs Fage, adding that the department was always happy to give advice if a home owner is unsure.

In many cases, provided the asbestos is undamaged, it is not necessary or realistic to remove all the material, although it may require sealing.

Ultimately, all the Island’s asbestos ends up in sealed bags in the shipping containers at La Collette. Unfortunately, and despite repeated calls for their disposal over a number of years, Transport and Technical Services have failed to come up with a solution – and whatever is decided is likely to cost millions of pounds.

‘Health and Safety do have oversight, because it is a place of work, and it is very much under active debate,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘It is not a risk – but the material is still there. The hard decision has still to be made.’