MANY weeks after the arrest, Nick Whitcombe would find himself sitting in a prison cell in La Moye, crying so hard into his bowl of cornflakes that the milk tasted of salt.

Being surrounded by police officers and placed in handcuffs during a pub lunch in St Helier had been a shock. Neither he nor his associate had known that detectives had been watching their movements.

The associate – the Jersey-based dealer of the operation – had been under surveillance for some time. And Mr Whitcombe, who had arranged for the drugs to be sent by post from his base in Merseyside, had been monitored from the moment he had stepped off the flight from Liverpool for a short visit earlier that day.

The arrest, in June 2014, was a turning point in the life of this former community-minded Wirral resident, who had made a name for himself in the parkour freerunning movement in his youth, before turning to bodybuilding and being drawn into to Liverpool’s underworld.

After the arrests, officers found a small amount of class B drug mephedrone, known on the streets as meow meow, at the house in the Island where the Jersey-based dealer was staying.

According to Mr Whitcombe, the associate told the police everything they wanted to hear – what they had been doing, that other drugs had been sent by post and that there were class A drugs, too.

Mr Whitcombe says the associate painted him as a major player in the Liverpool drugs scene – a man who travelled the world and who the police would never catch. The associate even claimed that an innocent friend who accompanied Mr Whitcombe on the flight to Jersey was his personal bodyguard.

‘He was never my bodyguard and the bit about me travelling the world – he had got that from seeing pictures on social media of my freerunning parkour days. But to the police it looked juicy.’

The associate was charged and remanded in custody, but Mr Whitcombe and his friend returned to Merseyside after being released on bail.

Several weeks later the then 23-year-old, now hoping that the States police would lose interest in him, was trying to get back to some sort of normality.

He had informed his solicitor that he would not be returning to answer bail in Jersey. ‘If they want me, they are going to have to come to get me,’ he told the lawyer.

If Mr Whitcombe had hoped the States police would move on, he was to be disappointed. Several weeks after informing his solicitor of his non-compliance, the lawyer phoned with bad news.

‘He said “I have just spoken to Jersey police and they have got a European arrest warrant for you and they are coming to get you”.’

But the game was not quite over yet. Placing his car and clothes in storage, he went on the run, spending four weeks in hotels in the north-west of England while still hoping the States police would eventually give up.

‘Four weeks in hotels sounds glamorous but it is dire. You are watching the same telly on a crappy TV and eating the same three meals off room service. It was not pleasant at all. It was extremely lonely,’ he says.

But there was still no sign of the Jersey police. Mr Whitcombe had no idea what evidence the force had on him. They had not been to his house. Or his mother’s house. Or his nan’s house.

It was enough to bring him out of hiding.

He moved back into his mother’s home and laid down the strict instruction: ‘Whatever you do, don’t answer the door.’

As it turns out, she didn’t really have a choice. About a week later Mr Whitcombe was woken by the sound of his mother screaming at the police. Downstairs were three Jersey officers and 12 more from the local force.

On the parkour scene he had been adept at getting himself out of scrapes, and during his days working as a nightclub doorman he called the shots. But here, standing in a living room packed with police, he had nowhere to turn. And he would soon discover the answer to the question of whether the States police had actually got any evidence to use against him.

‘I told my mum to calm down because she wasn’t helping anyone. And then I heard one of the Merseyside police ask the Jersey police if they needed my mobiles and my computers, and the sergeant’s response was “no they don’t need any of it, they have more than enough already” and it was at that point when I realised there’s no point in trying to be a smart**se and making stuff up anymore.’

He was flown back to Jersey to find that the investigating officers were indeed awash with evidence: pictures of the drugs, GPS co-ordinates of where the images had been taken, phone records, tracking references for the parcels. They had it all.

He stayed the night in the custody suite in St Helier and the following day – his 24th birthday – he spent his first night in a proper prison cell.

With his only experience of prison being watching The Shawshank Redemption and the US drama Prison Break, he spent the first few weeks trying to come to terms with facing a jail term he assumed would be somewhere between 12 and 18 months.

He may have been well-versed in sentencing policies in the UK, but this city kid was, it seems, naïve to the Royal Court’s attitudes towards organised drug trafficking.

‘A prison officer came to me one day and said my advocate was on the phone. At this point I didn’t know what an advocate was. I picked up the phone and she said that there had been some more charges. I asked her what I would be looking at and she said “I’m sorry to inform you that the maximum for this is 14 years”.

‘Everything just went “whoosh” there and then. I had never been in jail before and now I was facing this. I went back to my cell and I had some cornflakes in a plastic bowl and I remember eating them and crying and the milk tasted of salt and I was laughing at the situation at the same time.’

This one-time parkour star was now facing years in La Moye, with a fraudster in the cell at one side, and Darren McCormick, who murdered a man with an axe, on the other.

He may have struggled to comprehend the sort of people he was now residing with, but he had to do his best to get along with them. He says that neither he nor McCormick were allowed off the wing – McCormick because of the nature of his crime, and Mr Whitcombe because the authorities believed that his parkour past made him an escape risk.

‘They thought I was going to hop the fence and run away somewhere. Don’t get me wrong, if we were in the middle of Liverpool maybe, but I didn’t fancy swimming the Channel,’ he says.

Recalling his time with McCormick, who was responsible for one of the most horrific crimes in the Island’s history, he says: ‘We were both cleaners on the wing and one day I had a conversation with him about what happened.

‘He said he couldn’t remember doing what he did. I remember one day we were playing Scrabble downstairs, just me and Darren, and I had done a word down and it had an ‘e’ in it. And he then does a word across, A X E D. And he just looks at me as if to say “your go”. It didn’t even register with him until I pointed out what he had done. That’s one word that should have been out of his vocabulary for the rest of his life.’

Mr Whitcombe pleaded guilty and was jailed for six years, and did ten months in La Moye. He was then transferred to HMP Liverpool, where he spent a further two-and-a-half years before being released. The Jersey-based associate was jailed for three-and-a-half years. The innocent man who accompanied Mr Whitcombe to Jersey was released without charge.

During his time in Jersey’s prison Mr Whitcombe began to realise when it was, and how it was, his life had gone wrong. He was helped by a visual aid – a large rectangular board on the wall where prisoners can place their photographs. In the first few weeks and months, the board was covered with images of flash cars, champagne parties and ‘friends’ he had made during his new life.

The first few weeks, maybe even the first couple of months, letters regularly arrived from those featured on the wall. But as each week passed, the maildrops became less frequent: fewer letters from fewer people.

By the time he reached the end of the third month, he started sending letters to his old friends – the ones he made before his descent into drugs – and once again mail, often including photographs, started to be slid under his door.

‘Over the next three months I began taking down the first photos I’d put up, a couple photos a week, and replacing them with the photos sent in by my old friends.

‘Month five is when it hit me; somehow I’d not even acknowledged the slow transformation of my photo wall and it came as a sudden realisation one day when I was lying in bed looking at them. All the new “friends”, the money, cars, parties, had all disappeared and I was left with what were clearly most important to me – my original life and those within it. It seems almost obvious now; I spent my entire teenage life happy and content. I’d over-achieved, then I entered the “other” world and my life was consumed by power, control, violence, money and drugs, and I was utterly miserable.’

Mr Whitcombe has nothing but praise for La Moye and its staff. ‘Jersey cons should be grateful for what they have when you compare it to prisons in England,’ he says.

In the final 18 months of his sentence, after being transferred to the UK, Mr Whitcombe was allowed to leave prison for six days a week to work for a social enterprise called Recycling Lives. His rehabilitation in the community was now beginning in earnest.

He had already progressed through the UK prison system fairly quickly, spending his time as prison rep for the Drug and Alcohol teams and helping prisoners in a one-to-one format.

Shortly before he was released, he made the first big stride into a new business venture which would ultimately see him make headlines across the world.

He bought a stake in a bodybuilding gym – in once-vacant premises at the top of the road he grew up in – which was owned by an old friend who was retiring. Mr Whitcombe was left to run the business, called Body Tech, and set about life with the ultimate goal of buying the gym outright.

‘I halved our outgoings, which were huge, took down walls, ceilings, worked into the twilight hours most nights, changed the facility from 8am to 10pm to 24/7 to compete with neighbouring corporate gyms. We excelled. The amount of direct-debit members almost doubled, and I successfully acquired 100% of the business within a year of being home. The two years that followed we have grown month on month; the business today is worth over £250,000,’ he says.

‘Since coming home I’ve made it a priority to return to the person I was pre-2012 and do some good in the world.

‘I now own the gym, a clothing brand and we are launching a digital community health app next month. Everything we do is community-focused.’

It is this passion for the community which fired Mr Whitcombe into action in October last year, when Liverpool became the first region in England to be placed in lockdown tier three.

Despite published legislation stating that the closure of gyms would be left to the discretion of local authorities, PM Boris Johnson announced they were to close.

Mr Whitcombe spoke to the local mayors and MPs, who said they had not been given a choice. And so he and about 70% of gym owners in Liverpool vowed to keep

their doors open and face the consequences.

‘It was never a reckless decision – we knew from the government’s own published data that gyms only accounted for 1.7% of the national infection rate.

‘We all know the health benefits of being fit and healthy and therefore the importance of our sector in alleviating the strain from our NHS. We had to take action for the health of our customers.’

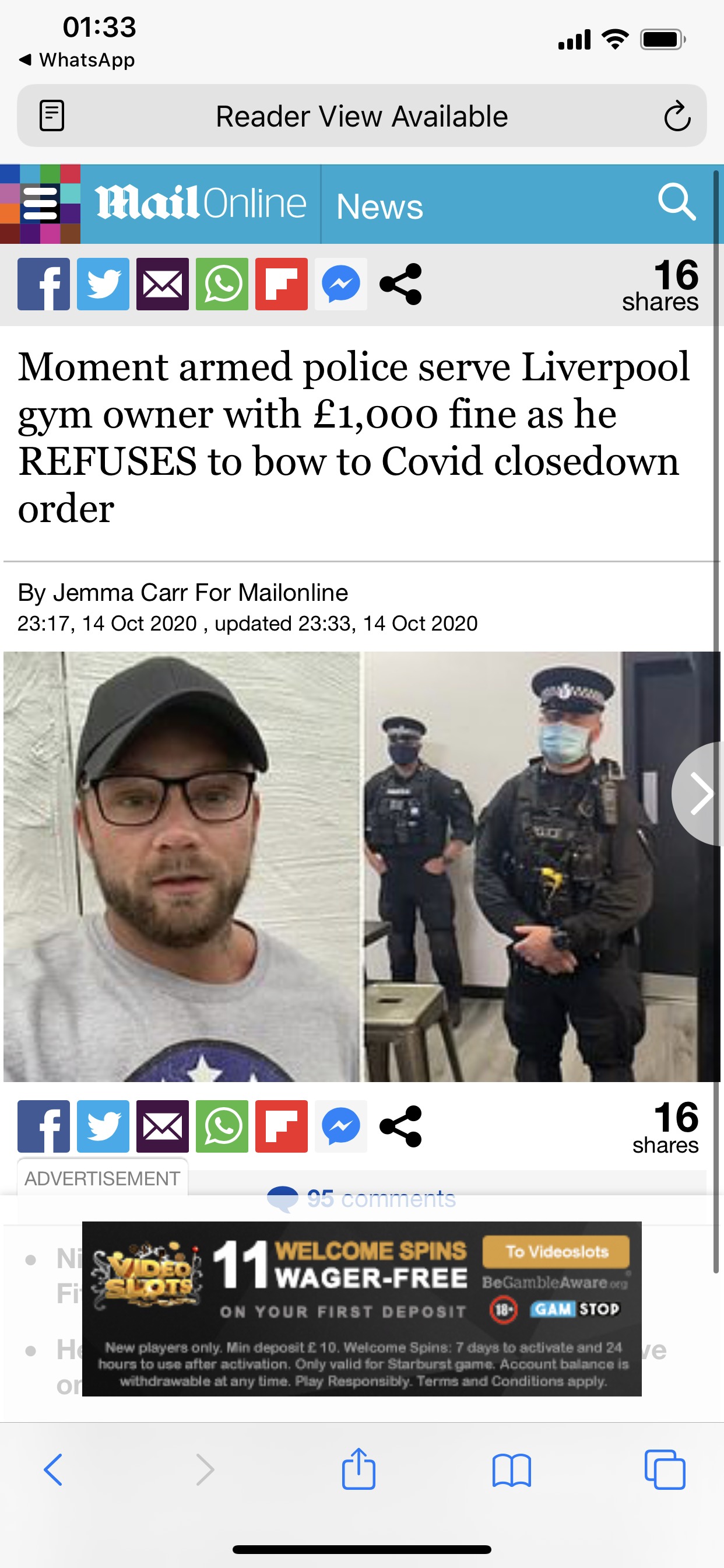

On day one, eight police officers visited the premises and, according to Mr Whitcombe, apologetically asked him to close. He didn’t and was later fined £1,000. The visit provoked a tide of support for Body Tech and other gyms in the city. A video of Mr Whitcombe describing the police visit was viewed eight million times in just over 24 hours and he soon found himself featuring in the national media, as well as CNN and the New York Times.

More than £53,000 was raised in a GoFundMe campaign to pay court fees – all of which Mr Whitcombe says he will instead give to mental-health charities.

A petition calling for gyms to be allowed to reopen gained 650,000 signatures, and on Mr Whitcombe’s 30th birthday, on 23 October, the government reversed their decision.

He has since become an ambassador for a sports nutrition brand, received a handful of community awards and a nomination for the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Unsung Hero award.

It’s a life far removed from the one he had during the dark days of 2014, and he is acutely aware that it was the arrest, and the photoboard on the wall in his cell, that were instrumental in bringing him here.

‘My life is the best it has ever been and I’d never have reached this point had I not had the wake-up call I did.

‘Don’t get me wrong, I wish none of it had ever happened in the first place, but in a strange way I am actually really grateful for being sent to prison,’ he says.