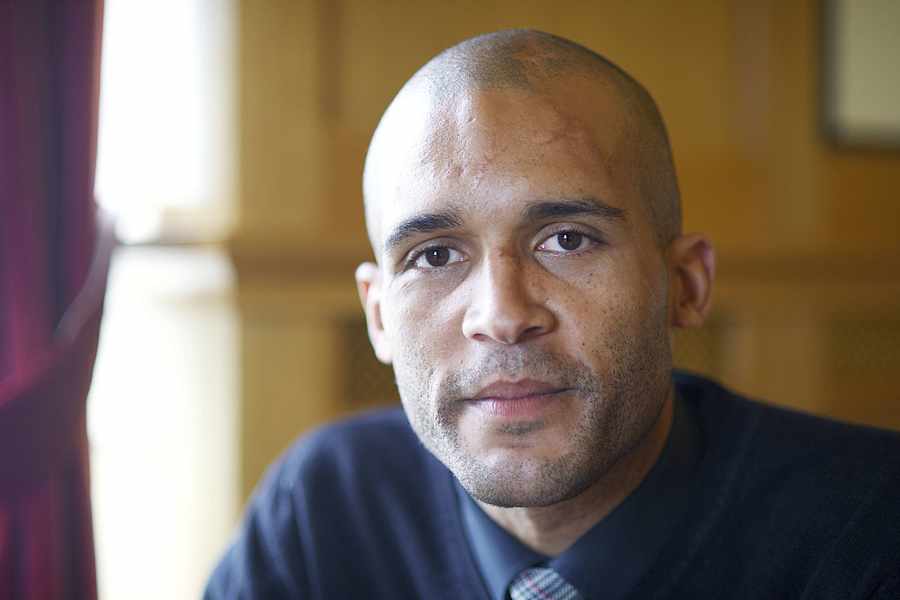

To mark World Mental Health Day today, former Premiership footballer Clarke Carlisle talks to Krysta Eaves about his ten-year battle against depression and two suicide attempts

FOR Clarke Carlisle, talking about what happened last December is as easy as talking about the weather.

‘I made the decision to kill myself’, says the 35-year-old former Premiership footballer.

He still bears the scars from his suicide attempt, when he jumped into the path of a 12-tonne truck travelling at 60 mph, and says there are still days when he struggles with his depression.

But although previously they were topics that would be brushed under the carpet or spoken about in hushed tones, Mr Carlisle says that mental health and depression no longer hold a stigma for him.

‘I find it as easy to talk about my story as I do to talk about the weather,’ he says while sitting in a quiet bar at the Hotel de France, shortly before addressing a conference on mental health organised by the Jersey Employment Trust and Mind Jersey.

‘That’s not to say it isn’t emotionally taxing to run through such emotional experiences as two suicide attempts, life-saving surgery and the emotional impact on family and friends.

‘It is emotionally draining, but I believe it is of paramount importance that people do normalise talking about these issues.’

Although the former Leeds, Burnley and Watford player now champions the importance of discussing mental health, he admits that it was a subject he previously knew very little about.

‘I was living with depression for about ten years,’ he said.

‘I didn’t talk about it. I didn’t know about it.

‘I was totally ignorant to the possibility of mental health issues. I had never been educated about it.

‘I had never been told what signs to look out for.

‘If you are not aware of something, how can you know you’ve got a problem?’

However, citing the statistic that one in four people is expected to suffer from a mental illness at some point in life, Mr Carlisle stresses that it is a condition that can affect anyone from any walk of life.

‘Depression is indiscriminate,’ Mr Carlisle, father to Francesca (16), Marley (7) and Honey May (5) said.

‘My bank balance, my material status, my football, all these things are largely irrelevant.

‘It doesn’t matter what industry you are in.

‘I could have been unemployed, a single father, a nurse, a teacher.

‘There could have been a circumstance that could have triggered my journey.’

Although his suicide bid last December was played out in the national media, his previous attempt at the age of 21 after suffering a serious injury on the football pitch was something that was kept secret.

‘I had just moved to QPR and was enjoying the bright lights of London,’ he said.

‘I had just broken into the England under-21 team. It was the fulfilment of my childhood dreams.

‘Then one innocuous tackle took all that away.

‘The surgeon thought I wouldn’t be able to walk without a stick, let alone play football.

‘I had just made that step into my dreams, and to have that all taken away through no fault of my own, I couldn’t process that.

‘I couldn’t deal with it. At that time, football was my life, it was my identity,

‘When I tried to process that it was all gone, I figured I was of no use.

‘I tried to kill myself with an overdose.

‘Fortunately for me, my girlfriend at the time came home unexpectedly, found me and got me to hospital, where I had my stomach pumped.’

Although the physical effects of his overdose were treated, Mr Carlisle says the emotional ones were not.

‘I was discharged without seeing a psychiatrist,’ he said.

‘That was the attitude at the time. I didn’t even tell my parents.

‘My girlfriend’s family said: “Just crack on, we don’t talk about it”.

‘Having gone through such an emotional thing, I then locked it into Pandora’s Box without picking through the guilt, the shame and the feeling of failure that I’d been unable to kill myself.’

And he said that not seeking help led him to routinely spiral into self-destructive behaviour.

‘Not dealing with my emotions manifested in my exploding from time to time – drink binges, total isolation, almost hibernation from society,’ he said.

‘It was cyclical. Every six months I would self-destruct in some way, not understanding that there was an illness underlying it.

‘My partner, my family and I all questioned why was I not fulfilled or happy or content.

‘All these questions were coming from the perspective that I was well.’

It was not until 2010 that he was diagnosed with depression.

‘It was through my wife. She was suffering from post-natal depression,’ he said.

‘I couldn’t understand it. I adopted the attitude, what the hell is wrong, woman?

‘Burnley had just been promoted, work was a success, we had a fantastic life, we now had a beautiful child, a beautiful home. I thought, what have I got to be depressed about?

‘But my ignorance led to arguments, and she implored me to read up about it.

‘I read the indicators for depression and realised that it was a description of me. I phoned my doctor.’

Despite his diagnosis, Mr Carlisle, who now lives in Catterall, Lancashire, says he would not stick with his medication and would fall into bad patterns.

‘Things came to a head on 22 December last year, two days after he was arrested for drink-driving.

‘I made the decision to kill myself,’ he said. ‘I thought my family and children would be financially stable, that my wife would no longer by burdened with my scurrilous behaviour, that my parents would no longer be ashamed of this black sheep of a son, that my siblings would no longer be embarrassed by me.

‘I jumped in front of a truck on the A64 doing 60 mph.

‘I’d overridden that natural basic human instinct to survive.

‘Until you’ve crossed that line, you can’t comprehend it.

‘I came to 30 seconds later in the middle of the road. I opened my eyes.

‘Blood was trickling down my arm.

‘I couldn’t believe I had failed again. I was devastated.

‘That didn’t change for the next six to ten days.

‘I was still in that place when I was desperate to be dead.

‘Even when my wife and my family were in and out of hospital, I was still saying to them: “I don’t want to be here”.

‘I can’t imagine how traumatic that was for them to hear, but I’m so glad I said it because if I had started on a journey of covering it up again, I would not be here now.’

After being treated for his physical injuries, Mr Carlisle – a former chairman of the Professional Footballers’ Association – was admitted to the Cygnet Hospital in Harrogate for six weeks, where he received specialist mental health support.

Today he says it is due to medication, counselling, therapy and support networks, as well as a huge onus on himself, to ensure that his mental well-being remains healthy.

Some days are tougher than others, but he says it is nothing short of a miracle that he did not die last December, and now sees it as his duty to raise awareness to others about mental health.

‘It’s a miracle. I will not hesitate to say that,’ he said.

‘I believe God spared my life so that I could help as many other people as possible.

‘If I can help one person, that is a good day’s work for me.’