Historian Doug Ford continues his journey around our coastline

THE cliffs beyond Vicard Harbour toward Petit Port were called the Long Bank in the 19th century. Today the north coast cliff path follows it.

At Petit Port there is a small cottage, originally built in the late 18th century as a guardhouse, with a one-gun battery close by. Today it is maintained by the Jersey Canoe Club.

A stone nearby commemorates Operation Hardtack 28, the only British Commando raid on the Island during the Second World War.

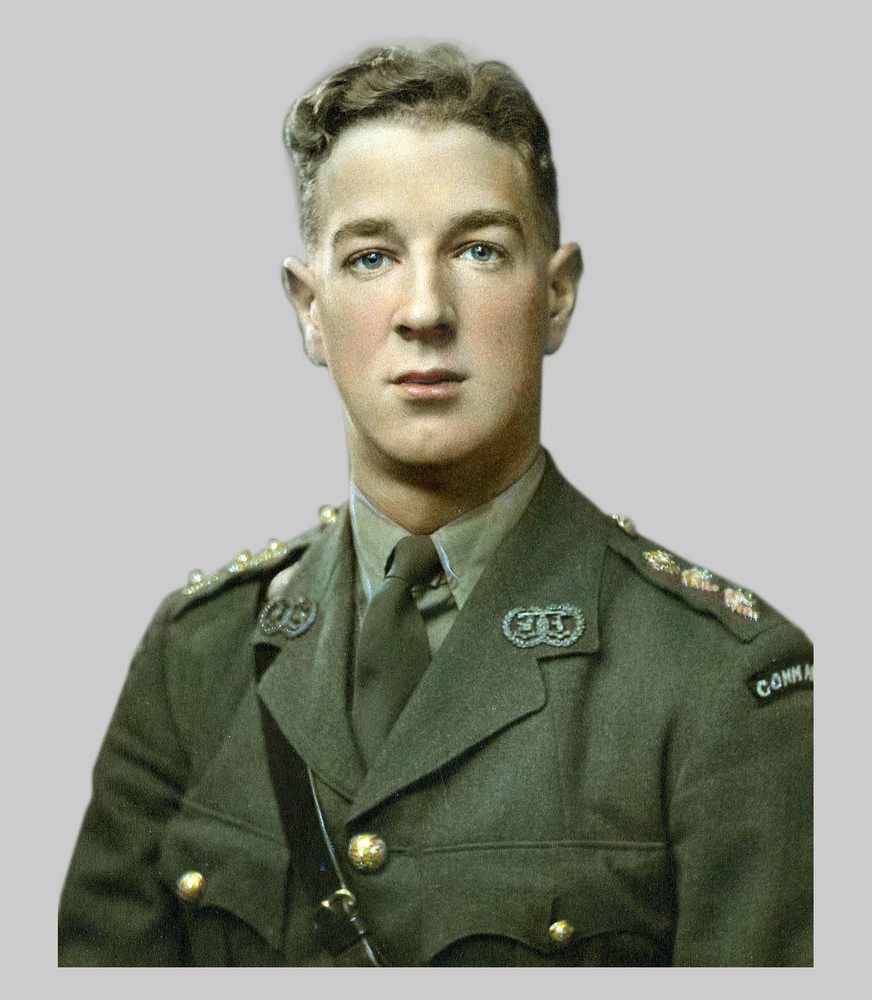

Led by Captain Philip Ayton, a party of British and French commandos of the Special Boat Service landed here on 25 December 1943 in order to gather intelligence.

Sadly, Ayton stood on a mine as the group were making their way back to their boats and died of his wounds back in England.

Pigeons and caves

Just offshore is Les Rouaux, which means a narrow channel between rocks and probably refers to the passage between the cliffs and the offshore reef known as Les Sambues.

A couple of place names on these cliffs refer to features that are no longer part of Island life.

Rising from the middle of the bay is Le Cheval Guillaume, said to be a demon turned to stone.

Local tradition had it that anyone rowing around the rock on the Feast of St John (24 June) would be ensured good luck for the next 12 months.

La Colombière means a place where pigeons could be found and is a reminder of the importance of pigeons as a food supply.

Further along is La Crâne, which was where the local farmers fixed a winch on the cliff-top to haul up vraic to spread on their fields from small boats anchored below.

A bit of elbow grease here saved a cart journey of over a mile from Bonne Nuit harbour.

Close by and half way up the cliff is a spring – Fontaine des Mittes – which was believed to have healing properties.

The headland is Belle Hougue, which, with its associated tide race and accompanying waves breaking over the offshore reefs, is the highest headland in Jersey and probably the most dramatic.

On its western side are the Belle Hougue caves.

Although locals knew of them, they were only ‘officially’ discovered in 1914 when Jesuit scholars from what is now Highlands College recorded stalagmites and stalactites inside but more importantly the antlers, teeth and bones of a small sub-species of red deer unique to the Island (Cervus elaphus jersiensis).

To the west lies Giffard Bay, which takes it’s name from the Giffard family.

Halfway around the bay is the boundary between the parishes of Trinity and St John.

This is the first ‘beach’ after Bouley Bay.

Where the bodies wash up…

Beyond the rock known as Long Echet is L’Homme Mort which probably got its name because this was an area in which bodies were washed up.

In June 1894 the headless body of a man was found floating here.

Naked apart from a scrap of shirt it was never determined who he was or where he had come from.

Six years later, a lifebuoy attached to a ship’s ladder belonging to the SS Amaryllis of North Shields was recovered here.

She had been lost off Ushant seven days earlier.

Other accidents were more local.

In August 1860, following their success in the St Helier Regatta, Philip Hamon and, his brother-in-law, John Arthur had sailed back from town only to be hit by a squall as they were coming in to land at Bonne Nuit.

Both men drowned within yards of their homes.

Giffard Bay is separated from Bonne Nuit Bay by a small headland called La Crête – the crest; what the Hull Daily Mail described in an editorial in June 1920 as ‘a natural breakwater of rock’.

A small boulevard housing cannon is shown here on the 1563 Popinjay map and the Duke of Richmond map shows a couple of batteries and a guardhouse here at the outbreak of the French Revolution.

The current building dates from the 1830s when the States spent just short of £1,000 to create a small fort capable of commanding both Bonne Nuit to the west and Havre Giffard to the east.

However, within 25 years the fort had lost its military importance because of a treaty of friendship between France and Britain.

It was re-armed during the Occupation, when the occupying forces sited a 37 mm PAK anti-tank gun, a heavy machine gun, two light machine guns, a mortar and a 300 mm searchlight here.

Today it is a self-catering holiday let administered by Jersey Heritage.

Good or bad night?

It has been said that until the middle of the twelfth century the bay was referred to as Mal Nocte – Bad Night, but this may refer to the anchorage as in a few old maps the sea beyond Bonne Nuit is called Maurepos (ill repose).

In 1150 when Guillaume de Vauville gave a chapel here to the Abbey of St Sauveur Le Vicomte in Normandy it was referred to as Ste Marie de Bono Nocte – although, just to confuse matters, a few years later his son sold a field which was referred to as being ‘alongside the Chapel de Mala Nocte’. So who knows!

Legal and illegal cargo

Just below La Crête this area of Bonne Nuit Bay was known as Le Havre Jean de Gruchy for a short time although the earliest documents refer to the whole bay as the haven of St John.

Jersey was supposed to have been converted to Christianity by Saint Marculf around 540 and one of the first religious communities to be set up was here at Bonne Nuit.

It lasted until the mid-ninth century when it was supposed to have been destroyed by the Vikings.

In 1685, the bay was described as being used by boats that frequented the other islands; 44 years earlier Thomas Chevalier was noted as keeping his sloop in the bay, probably for this very purpose.

The harbour itself was only built by the States in 1872 when Thomas Le Gros was awarded the contract to build a pier for the 15 to 18 boats and 80 fishermen fishing out of Bonne Nuit. The main catch was lobster and conger eel.

The year before, a Chamber of Commerce report into the fisheries heard evidence from a Mr Remon who told them that that there was plenty of fish in the area and a proper harbour would allow the fishermen to increase their catch because it would enable larger boats to be used.

Remon obviously knew what he was talking about because the previous year (1870), along with his two brothers, he caught 2,240 lb of conger in one day from their boat, La Lumière using long lines.

Although the Guernsey newspaper, The Star, described the catch as unprecedented, the fisher folk of Bonne Nuit knew different because in October 1856 Remon’s father and a Mr Roberts had caught 2,308 lbs of conger eel in a single day from the same small boat.

In 1836 the Eliza, a 113-ton brig owned by Philippe Winter Nicolle, sailed from town bound for the nearby port of St Germain.

The master made a short detour to Bonne Nuit where he loaded a cargo of 2½ tons of tobacco plus cigars, snuff and casks of spirits which he delivered to the Welsh port of Fishguard before making his way to his original destination in Normandy where he loaded his legal cargo of 32 sheep bound for the butchers of St Helier.

Gradually over the 19th century, probably because the guidebooks described it as a ‘gem of seclusion’, the bay became more popular with tourists and so the more clandestine activities associated with the bay were forced to stop – too many prying eyes.