But, the wartime heroics of some of the Broad Street postmen are among the great resistance stories of the Occupation’s moral quagmire.

As some Islanders with personal grudges wrote anonymously to the German authorities to denounce their neighbours, the men responsible for delivering those letters did everything they could to ensure that their treacherous contents never arrived – or arrived too late, once the victims had been forewarned.

Proudly wearing the insignia of the Royal Mail – Jersey did not have its own independent postal service until the end of the 1960s – the posties applied their own ethics to the business of delivering wartime mail, a story told by former postman Dave Vautier in The History and Stories of the Jersey Post Office.

Researching the book, Mr Vautier recalls being told many stories of the escapades of his wartime predecessors.

‘Postmen had the ideal opportunity to stop these letters and the easiest way to do it was to put them in the boiler,’ he said. ‘Often they’d be written by somebody who wasn’t that well educated, judging by the handwriting, so they would have a good guess about the contents. They would steam them open and then, if there was nothing, they’d let them go on. But if the Germans weren’t expecting a particular letter they wouldn’t miss it, so it was an easy thing to destroy some of them.’

Letters which were not burned would be held back for three days before they were date-stamped and then delivered in the normal way. In the meantime, the postman on his rounds would have warned the recipient that a search was imminent, and the radio or other forbidden commodity would be temporarily relocated somewhere else.

A more individual approach adopted by one postman went unrecorded until Mr Vautier included it in his book published in 2007: ‘Equally brave were the actions of Harold ‘Peddler’ Palmer, who retired during the 1960s…Some time after Harold’s death, his son was sorting the contents of his house, and hidden in a drawer of a desk, he came across bundles of mail, all of which were addressed to the German occupying authorities.

‘The contents were such that it was obvious they had been sent by Jersey residents in the hope of informing the Germans which Islanders had been listening to the BBC news, which of them had been perhaps hiding livestock – the existence of which had to be reported to the authorities – or given an escaped prisoner shelter. Incredibly, according to Harold’s son, some of the authors of these pathetic epistles had even signed their names.’

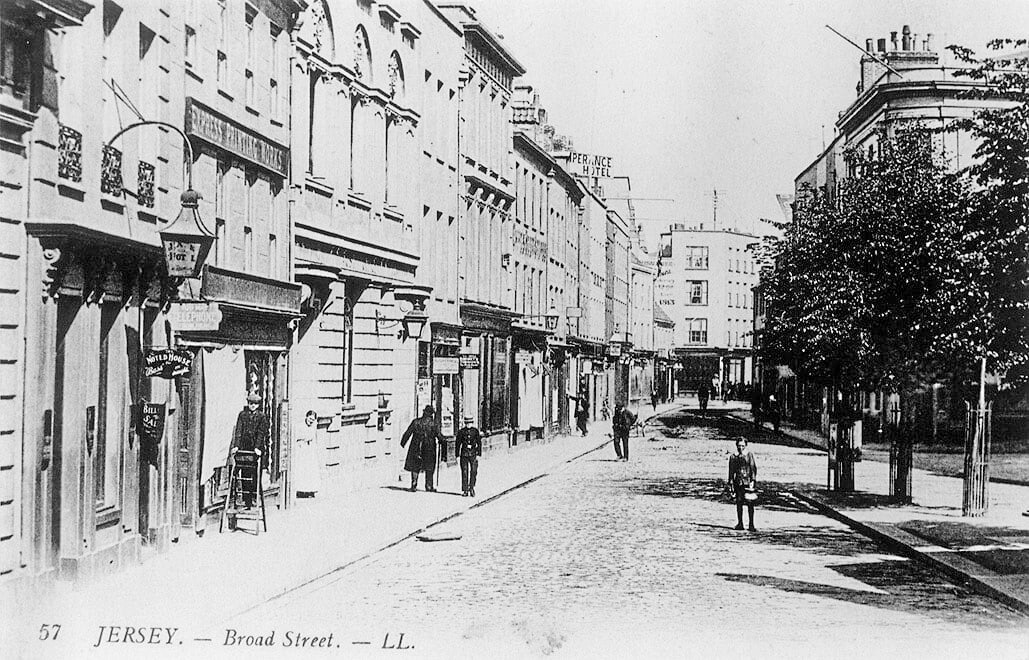

During the Occupation, the Royal Mail operated out of the Broad Street premises that remain Jersey’s main post office, with the mail being sorted on the premises for distribution by the team of postmen. According to Mr Vautier, the boiler used to destroy many of the letters remains on the premises, a poignant reminder of the days when a postman could interfere with the Royal Mail yet emerge with some honour in the process.