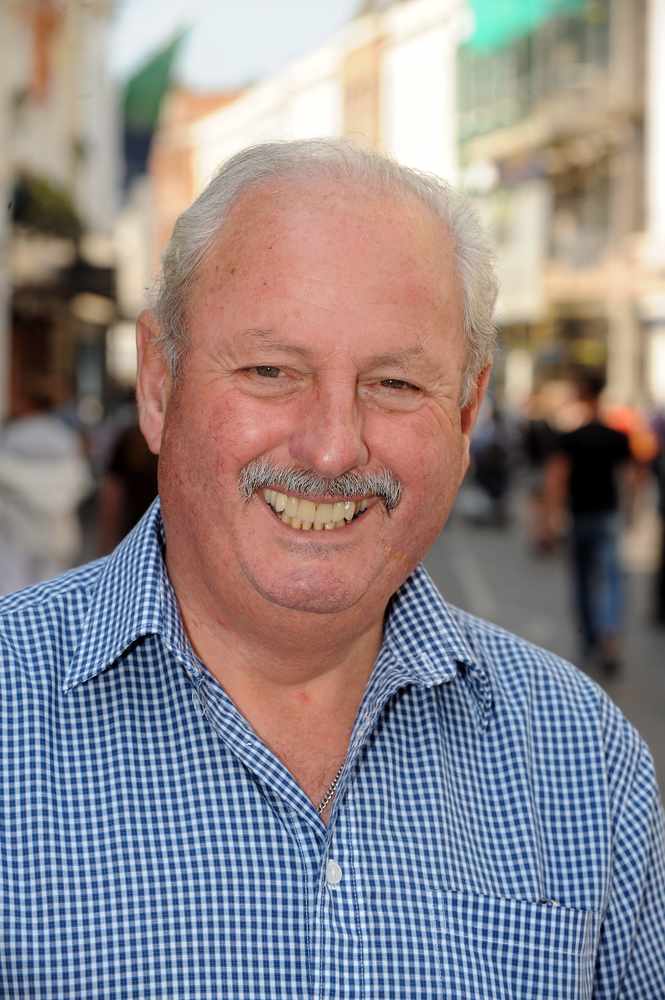

Derrick Frigot, who has spent more than 50 years promoting the Jersey worldwide, was ringside at the All-American Jersey Show in Louisville, Kentucky, on Monday, to see FLM Tradition Flower judged champion senior yearling in milk out of 43 animals from all over America.

Speaking to the Jersey Evening Post from America, Mr Frigot said the tension as it took more than an hour to judge such a big class was almost unbearable.

‘I was shaking with excitement all the time and I can’t find the words to describe how I felt when she was pulled out first,’ he said.

‘In all my career of working with Jersey cattle, and owning some champion cows, this was the biggest climax I have ever had.

‘It was wonderful and very emotional.’

This was FLM Tradition Flower’s third major title in just two months, which began in September when she topped her classes at the Western National Show and at the largest dairy cattle show in North America, the World Dairy Expo in Wisconsin.

See pictures and videos from Jersey’s recent Autumn Cattle Show here

Over that time she has travelled almost 10,000 miles by road in a specialist cattle transporter, with the Kentucky trip taking 50 hours each way.

Like all Jersey cows around the world, her roots can be traced back to the Island.

She comes from the Day Dream family, which is probably one of the oldest cow families as it dates back to the 1870s.

Today ‘Day Dreams’ can be found on dairy farms all over the world and in the Island.

Mr Frigot is the President of the World Jersey Cattle Bureau and he co-owns the cow with Lee Mahovic of Vancouver, Canada, and Ryan and Freynie Lancaster, who farm the Royalty Ridge Jersey herd in Tilamook, Oregon, on America’s west coast, where FLM Tradition Flower lives. The start of the cow’s registered name stands for the surnames of her owners.

Mr Frigot said that winning such a prestigious title at what is regarded among Jersey cow experts as the top show in the world would increase her previous value of £39,000.

‘But she’s not for sale!’ he said.

There are more than one million Jerseys in America and the population is increasing rapidly.

By 2020 they are expected to account for 20 per cent of the national herd.

JERSEY’S countryside, in all its variety, is our greatest asset but it is generations of Islanders who have worked its soil that have made it what it is today.

In exploiting the Island’s rich natural assets and ideal growing conditions, local families – many of whom can trace their roots back to William the Conqueror – have created a diverse rural landscape.

Finance may be the dominant factor in the Island’s economy but people don’t come here to see banks and office blocks no matter which top-notch architect designed them.

Nor do they come here because we’ve got superfast broadband or a growing digital sector; they come because of the environment, heritage and a worldwide reputation for top-quality dairy products and fresh produce.

As finance has gained in prominence, support for agriculture has diminished as politicians look outside the Island to further diversify the economy.

However, it is not all doom and gloom in the Island’s oldest industry.

A revitalised dairy sector, maximising the international reputation of the Jersey cow, is also looking outwards to exploit new markets with encouraging early successes.

The Jersey Royal remains the premier crop and the Island’s biggest export, but its production and profits are controlled by two of the UK’s largest agro-businesses and not in the hands of individual local farmers.

That may upset the traditionalists but it makes sense in terms of brand profile and marketing power in an industry driven by price and consumer demand for cheap food.

The reliance on a single crop has its downsides and a lack of rotation, threats from pests and disease, and the impact on water quality are issues the industry must address.

Integral to the countryside mix – and the Island’s food security – are the farmers who grow a variety of other crops and who have diversified into niche markets such as livestock and egg production.

Together, they will never be able to meet the Island’s demand for fresh produce but their activities are as vital to maintaining the Jersey way of life in an increasingly modern world as they are to keeping fresh local produce in the shops.

And there will always be a market for local produce, and not just from ‘foodies’ who frequent farm shops and roadside stalls, but also from the supermarket chains that dominate the retail food market.

Jersey’s farmers, in particular those who have the confidence to invest in the future, and the young generation embarking on careers in agriculture, need all our support to succeed – which is why the JEP is launching its Keep Jersey Farming campaign to back the industry.

Our campaign is not just about buying local; it is about reconnecting the public with a way of life that has defined and influenced local culture and the environment for centuries.

It will profile farmers, highlight the issues that affect the industry and promote seasonality and provenance.

Farmers are the custodians of the countryside, which is under threat from competing land uses and over-development.

They need your support to survive.

- During the second half of the 1700s many cattle from Normandy were shipped to Jersey, to be sold on to English markets after being pastured in the Island for a few months. Being sold on as Alderney cattle in England, they escaped the excise duty on cattle from foreign countries.

- In 1763, pressure was put on the States to stop this illegal trade, and it responded by banning the importation of live cattle from Normandy into Jersey, imposing heavy fines to discourage infractions.

- However, the law was not observed by some farmers engaged in this lucrative trade. It needed four more acts passed – the last in 1878 – before a stop was put finally to it. As the 19th century progressed, even cattle sent over to English shows were not allowed to return, and the trade of live animals within the Channel Islands was also prohibited.

- These laws – still in effect – have proved to have many benefits to the breed in the Island. It has served to isolate them from bovine contagious diseases and most importantly, it has enabled the breed to develop its purity and strengths.

- Island farmers have concentrated on developing their cattle from the limited local population, and their skill fixed the special characteristics of the Jersey, resulting in the breed we see today. But the origins of this strong, pure bred Jersey cow remain unknown.

- The late president of the World Jersey Cattle Bureau, Anne Perchard, believed that the breed’s characteristics of early sexual maturity, fine bone, thin skin and tolerance to heat meant that at one time it had been bred specially to enable the animals to thrive in a hot, semi-tropical climate.

- She believed this suggested a Middle Eastern origin, citing the existence of Jersey-type cows in Egypt and Morocco as support.