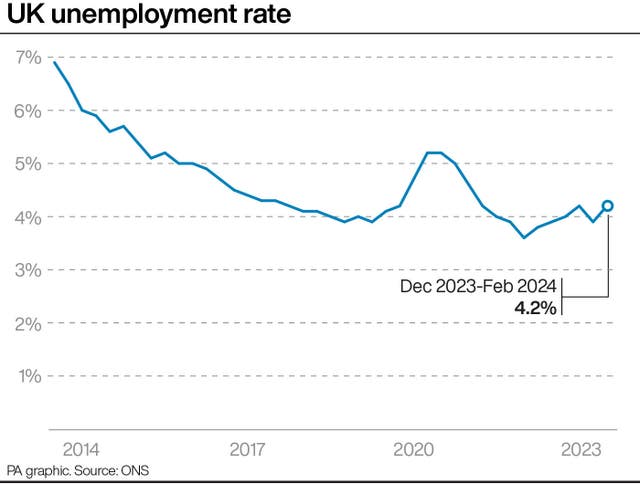

Britain’s unemployment rate has risen by more than expected and earnings growth has eased back once again in the latest sign that economic uncertainty is affecting the UK jobs market.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said the jobless rate jumped to 4.2% in the three months to February – the highest level for nearly six months and up from 3.9% in the three months to January.

Most economists had been expecting the rate to only edge up slightly to 4% in the quarter.

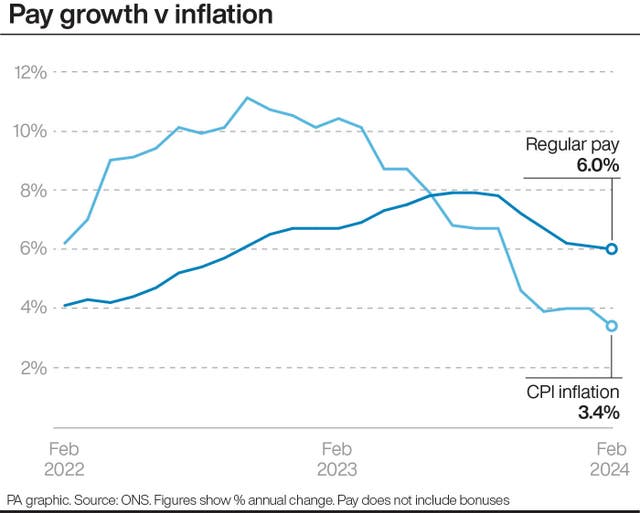

Thanks to falling inflation, when taking the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) into account, real regular wages rose by 2.1%, which is the highest for almost two-and-a-half years.

But the drop in earnings growth was less than expected, with economists pencilling in a fall to 5.9%.

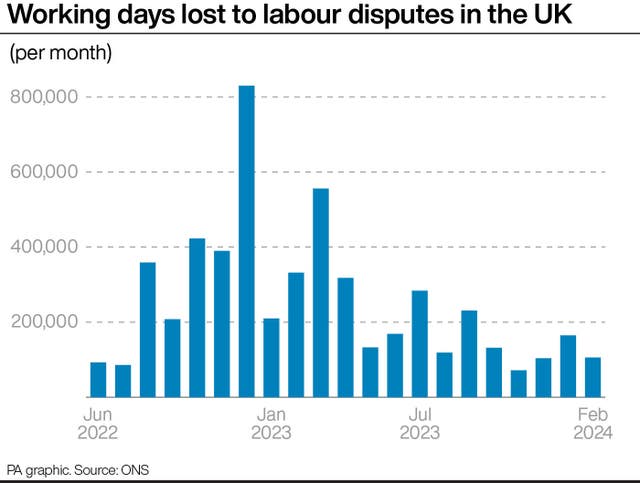

Rob Wood, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, said: “There is solid evidence the labour market slowed markedly in March.

“Rate-setters will take note.

“Wages lag labour market slack, so these figures will likely embolden the Monetary Policy Committee to begin cutting interest rates this summer.”

This is the biggest drop since the quarter to November 2020 at the height of the pandemic, although the figures are estimates and subject to revision.

Vacancies likewise fell, down for the 21st period in a row, off 13,000 quarter on quarter to 916,000 in the first three months of 2024.

The data comes after the UK fell into recession at the end of last year, although it is thought this may prove short-lived, with recent output data suggesting the economy is heading for growth overall in the first quarter.

Acting shadow work and pensions secretary Alison McGovern took aim at the Government, saying: “Tory failure is laid bare by the reality that we are now the only country in the G7 with an employment rate stuck below pre-pandemic levels.”

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt focused on the boost to workers’ pockets from rising real wages.

He said: “It’s great that real wages have now risen for nine months in a row, and, together with our national insurance cuts worth £900 to the average worker, people should start to feel the difference.”

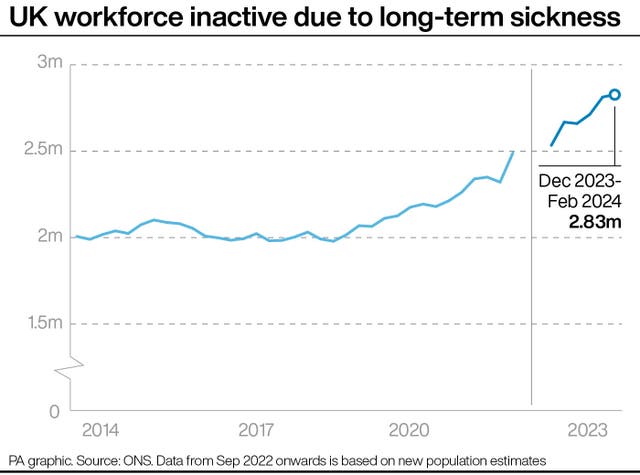

There was also some further gloom on inactivity in the UK, with the ONS estimating a 150,000 rise over the three months to February, taking the inactivity rate to 22.2%, its highest in more than eight years.

This was down to increasing numbers of students, but those classed as long-term sick climbed to a new high of 2.8 million.