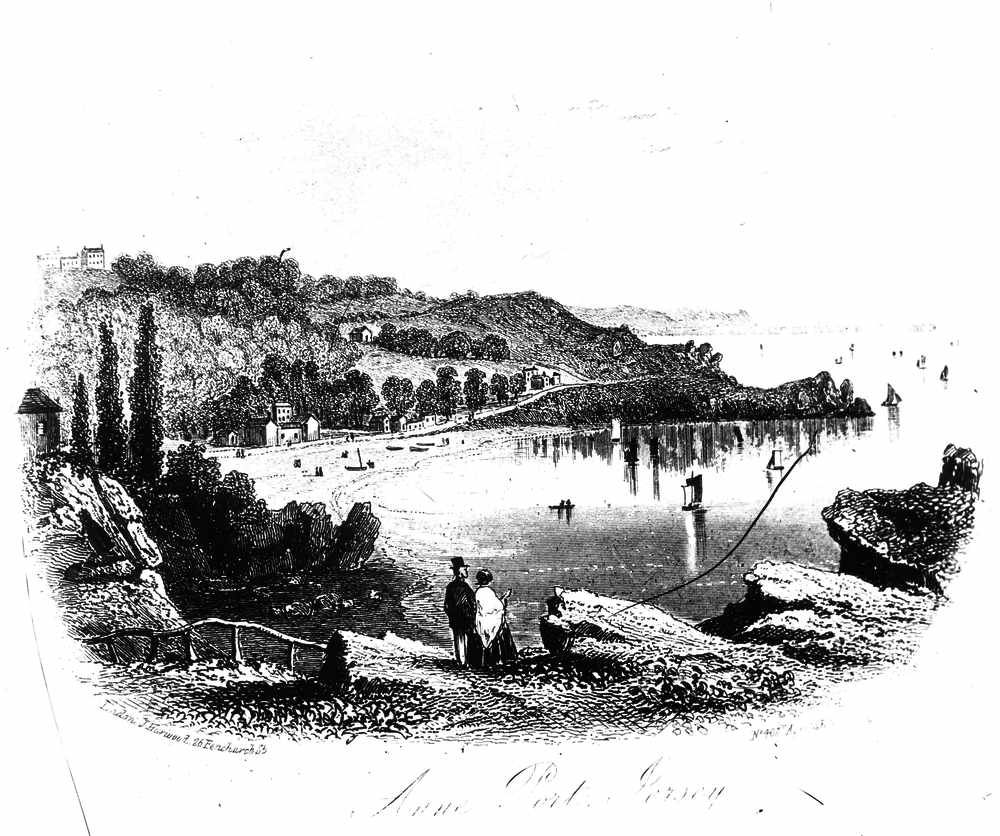

Historian Doug Ford continues his series celebrating the Islands coastline with Anne Port and Archirondel

Continuing northwards from Gorey Castle, La Route de la Côte follows the coastline to Jeffrey’s Leap before dropping down into Anne Port Bay.

It has been suggested that Anne Port was the main harbour on the east coast, possibly for the Island, before Gorey was developed.

The suggestion being that the name may come from the Latin Andii Portus, the port of Andium (the old pre-Viking name of the Island). In the 14th century the place was referred to as Andeport.

By the 19th century the bay was used by ‘… a couple of boats and few fishermen’ according to the 1872 Jersey Fisheries Survey.

The legend of Jeffrey’s Leap is well known to most Islanders although no one really knows who he was or even what crime he was accused of.

However, the rocky outcrop that now bears his name was reputedly an ancient place of judgment.

In 1901 the census shows the main fishing families were the Perchards living at Jeffrey’s Leap, the Le Huquets living by the slipway and the Noels who lived further inland.

The boats used by the Perchards and Le Huquets were painted white and had a single spritsail, whereas the Handy owned by Jack Noel not only had a mainsail and a jib but was also painted pink!

Like all potential landing spots in the Island, Anne Port Bay had its fair share of military installations to protect it. During the Napoleonic Wars there were gun positions – the North and South batteries – each with two 12-pounder guns on either side of the bay.

The North Battery was sited where the old Apple Cottage Tearooms (now demolished) were. In the renewed tension that grew after Waterloo the British government embarked on a new round of tower building and in 1837 the Victoria Tower, the last of the true martello towers to be built in the Island, was named after the newly crowned queen.

Its single 32-pounder gun set onto the roof had a range of three miles.

In 1860 the States spent £1,000 on improving the ‘military road’ from Gorey Castle to the tower at Archirondel, which included building a new road from Anne Port around La Crête to Archirondel.

A fortification was shown on La Crête headland on Richard Popinjaye’s map of 1563.

The granite slipway in the middle of the bay, La Montée d’Anne Port, was already there when the 1849 Godfray map was drawn.

It consisted of a low bulwark with cannon and a guardhouse to accommodate the gun crews and store the gunpowder.

It looked out over the small boat anchorage of Le Havre de Madolaine to the front and the more sheltered Havre de Fer on the Archirondel side.

In 1787 it was armed with two 24-pounder guns and in 1803 a document shows that a small detachment of one sergeant, a corporal and nine men of the 83rd Regiment were stationed here.

The battery was manned until the end of the French Wars and then it fell into disuse.

Archirondel

Originally a small detached rocky outcrop, Archirondel takes its name from the local family Rondel – Le Roche Rondel. In 1638 it is written as Roche Arondel.

Today it is best known for its distinctive red and white painted Conway Tower.

Work began on the tower in November 1792 and it was completed by 1794 by which time it had cost total of £4,000.

The overspend was paid for by cancelling plans for towers at Anne Port and Rozel.

By the late 1990s the cliff face beneath the old Apple Cottage was in danger of erosion and it needed to be protected so the base of the cliffs was reinforced by hundreds of tons of rounded grey and pink rocks.

These were brought over by barge from a quarry near Cork in Ireland.

In order to save money, instead of four machicoulis projecting from the top there are only three. Around the base of the tower Conway had a masonry gun-platform built to take four 18-pounder guns as well as the carronade on the roof. Because of these extra guns the tower was manned by a sergeant, corporal and 19 soldiers.

It was the last tower constructed during Conway’s lifetime and served as the prototype for La Rocco Tower in St Ouen’s Bay.

In 1847 the tower became joined to the rest of the Island when work began on the building of St Catherine’s harbour of refuge.

Originally, the idea had been to run a southern breakwater from Jeffrey’s Leap and enclose Anne Port Bay as well but spiralling costs meant the idea was modified and the start point for the southern arm was moved to Archirondel.

Once work reached the low-water mark the focus moved to building the eastern arm running out from Verclut (St Catherine’s). Work on the project was abandoned in 1852.

In July 1922 the States bought the tower and 700 square metres of land from the War Department for £200.

During the Occupation the tower was extensively altered when the original stairs were removed and concrete floors built while the battery was modified to take heavy machine guns.

Cliff rescue

Archirondel hit the national news briefly in 1927 when three women visitors had to be rescued from the cliffs.

Accounts of their escapade was reported in newspapers from Aberdeen to Cornwall.

Their cries for help attracted hundreds of people, many of whom were visitors.

Happily they were hauled up to safety through the furze and bracken whereupon, in the best tradition of cinematic melodramas, all three fainted into the arms of their rescuers.

A sticky end

News from Archirondel had also made the mainland journals in 1824 when, among others, the Southampton Herald and Dublin’s Saunder’s Newsletter and Daily Advertiser reported that a Mr Isaac Coutanche, of St Martin, had been judged to have destroyed himself through gluttony.

Coutanche had been in a public house near Archirondel Tower on 6 August when he ate six raw eggs mixed with two glasses of gin for a bet.

He then had another dozen raw eggs washed down with a pint of gin followed by some raw bacon and two glasses of brandy – all in less than 30 minutes.

Unsurprisingly, within an hour, he was insensible and he died two weeks later.

Ship in trouble

News of a more maritime nature tended to be reported only by the local press – such as the case of Matthew Gallichan’s 59-ton yawl London (Captain Cresswell) which ran into trouble just off Gorey on 5 November 1861.

She was on passage from South Shields to the Breton port of Le Vivier, near Cancale, when she got into trouble when a SSW gale blew up just as they were passing the Island.

In order to save the vessel Captain Cresswell ran her aground in Archirondel Bay.

His actions were successful as she was floated off soon after and taken into Gorey, where she had been built by John Messervy seven years earlier, for repair.

The London continued sailing from the Island until she was sold to foreign owners in 1872.