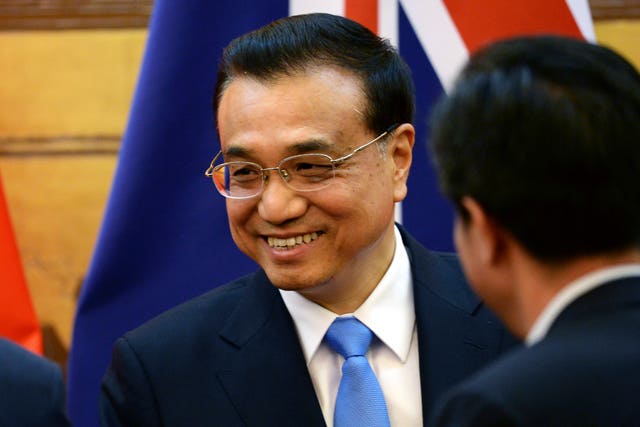

Former premier Li Keqiang, China’s top economic official for a decade, has died of a heart attack aged 68.

Mr Li was China’s number two leader from 2013-23 and an advocate for private business but was left with little authority after President Xi Jinping made himself the most powerful Chinese leader in decades and tightened control over the economy and society.

CCTV said Mr Li had been resting in Shanghai recently and had a heart attack on Thursday. He died at 12.10am local time on Friday.

Mr Li, an English-speaking economist, was considered a contender to succeed then-Communist Party leader Hu Jintao in 2013 but was passed over in favour of Mr Xi.

As the top economic official, Mr Li promised to improve conditions for entrepreneurs who generate jobs and wealth.

But the ruling party under Mr Xi increased the dominance of state industry and tightened control over tech and other industries.

Foreign companies said they felt unwelcome after Mr Xi and other leaders called for economic self-reliance, expanded an anti-spying law and raided offices of consulting firms.

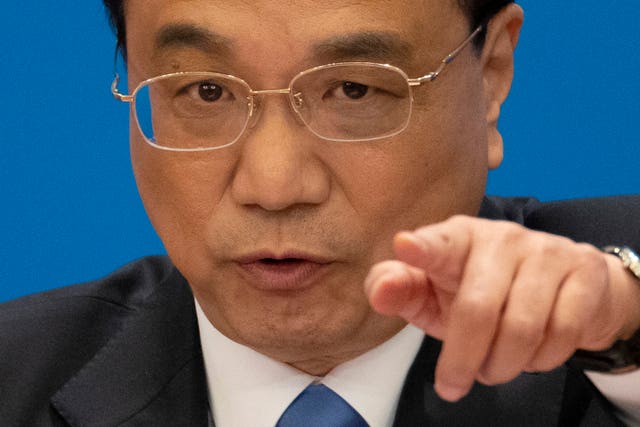

Mr Li was dropped from the Standing Committee at a party congress in October 2022 despite being two years below the informal retirement age of 70.

The same day, Mr Xi awarded himself a third five-year term as party leader, discarding a tradition under which his predecessors stepped down after 10 years.

Mr Xi filled the top party ranks with loyalists, ending the era of consensus leadership and possibly making himself leader for life.

Li Keqiang, a former vice premier, took office in 2013 as the ruling party faced growing warnings the construction and export booms that propelled the previous decade’s double-digit growth were running out of steam.

Government advisers argued Beijing had to promote growth based on domestic consumption and service industries.

That would require opening more state-dominated industries and forcing state banks to lend more to entrepreneurs.

Mr Li’s predecessor, Wen Jiabao, apologised at a March 2012 news conference for not moving fast enough.

In a 2010 speech, Mr Li acknowledged challenges including too much reliance on investment to drive economic growth, weak consumer spending and a wealth gap between prosperous eastern cities and the poor countryside, home to 800 million people.

Mr Li was seen as a possible candidate to revive then-supreme leader Deng Xiaoping’s market-oriented reforms of the 1980s that started China’s boom.

But he was known for an easygoing style, not the hard-driving impatience of Zhu Rongji, the premier in 1998-2003 who ignited the construction and export booms by forcing painful reforms that cut millions of jobs from state industry.

The Unirule Institute, an independent think tank in Beijing, said state industry was so inefficient that its return on equity – a broad measure of profitability – was negative 6%.

Unirule was later shut down by Mr Xi as part of a campaign to tighten control over information.

In his first annual policy address, Mr Li in 2014 was praised for promising to pursue market-oriented reform, cut government waste, clean up air pollution and root out pervasive corruption that was undermining public faith in the ruling party.

Mr Xi took away Mr Li’s decision-making powers on economic matters by appointing himself to head a party commission overseeing reform.

Mr Xi’s government pursued the anti-graft drive, imprisoning hundreds of officials including former Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang.

But party leaders were ambivalent about the economy.

They failed to follow through on a promised list of dozens of market-oriented changes.

Mr Xi’s government opened some industries including electric car manufacturing to private and foreign competition.

But it built up state-owned “national champions” and encouraged Chinese companies to use domestic suppliers instead of imports.

Borrowing by companies, households and local governments increased, pushing up debt that economists warned was already dangerously high.

Beijing finally tightened controls in 2020 on debt in real estate, one of China’s biggest industries.

That triggered a collapse in economic growth, which fell to 3% in 2022, the second-lowest in three decades.

Mr Li showed his political skills but little zeal for reform as governor and later party secretary of populous Henan province in central China in 1998-2004.

A Christmas Day blaze at a nightclub in 2000 killed 309 people.

Other officials were punished but Mr Li emerged unscathed.

Meanwhile, provincial leaders were trying to suppress information about the spread of Aids by a blood-buying industry in Henan.

Mr Li’s reputation for bad luck held as China suffered a series of deadly disasters during his term.

Days after he took office, a landslide on March 29 2013 killed at least 66 miners at a gold mine in Tibet and left 17 others missing and presumed dead.

In the eastern port of Tianjin, a warehouse holding chemicals exploded on August 12 2015, killing at least 116 people.

A China Eastern Airlines jetliner plunged into the ground on March 22 2022, killing all 132 people aboard.

Mr Li oversaw China’s response to Covid-19, the first cases of which were detected in the central city of Wuhan.

Then-unprecedented controls were imposed, shutting down most international travel for three years and access to major cities for weeks at a time.

In one of his last major official acts, Mr Li led a cabinet meeting that announced on November 11 2022 that anti-virus controls would be relaxed to reduce disruption after the economy shrank by 2.6% in the second quarter of the year.

Two weeks later, the government announced most travel and business restrictions would end the following month.

Mr Li was born on July 1 1955 in the eastern province of Anhui and by 1976 was ruling party secretary of a commune there.

He was a member of the League’s Standing Committee, a sign he was seen as future leadership material.

After serving in a series of party posts, Mr Li received his PhD in economics in 1994 from Peking University.

Following Henan, Mr Li served as party secretary for Liaoning province in the north-east as part of a rotation through provincial posts and at ministries in Beijing that was meant to prepare leaders.

He joined the party Central Committee in 2007.