- Jersey’s asbestos stockpile to be buried at cost of hundreds of thousands of pounds

- UK has refused to grant a license to all it to be exported

- How dangerous is asbestos? Find out more below

HUNDREDS of thousands of pounds is to be spent on burying Jersey’s asbestos stockpile after the UK refused to grant a licence to allow the toxic waste to be exported for disposal.

The waste has been stored in over 200 rusting shipping containers on the Waterfront since the 1990s, with environmental campaigners raising concerns that the double-bagged deposits of asbestos and builders’ rubble were a risk to public health.

Earlier this year Transport and Technical Services applied for a special exemption to ship the waste and at that time Transport Minister Eddie Noel said he thought the Island had a ‘reasonably good case’.

Sound insulation infill

Thermal insulation lagging

Felts, blankets, mattresses, tape, rope

Asbestos boards

Gaskets, washers, drive belts, conveyor belts

Roofing sheets and slates

Drain and flue pipes

Fascia boards, bath panels, ceiling tiles, toilet seats, cisterns

Damp proof courses, PVC panels and cladding

Lab bench tops, extraction hoods, fume cupboards

Brakes and clutches

However, the UK’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs have decided not to issue an export licence.

Deputy Noel said that his department was now seeking planning permission to use the area on reclaimed land at La Collette next to the containers to build a concrete-lined pit.

‘We will be meeting the Environment Minister, Steve Luce, about swapping the material over,’ he said.

‘We want to get this done as soon as possible.’

The minister confirmed that the sealed pit – which would measure around 30 metres by 20 metres – would cost around half a million pounds to build.

TTS director for solid waste, Richard Fauvel, said there were already some cells available, although these were regarded as temporary rather than permanent.

‘We need to get our heads together with Planning to work out the requirements,’ said Mr Fauvel.

‘Standard practice across the world is for secure burial.

‘There are some fancy processes, such as turning asbestos into glass, and we have investigated this, but it is not an overly-safe process because you have to shred the asbestos.

‘Also it is incredibly expensive to heat it up to the required temperature to produce glass.

‘Because the asbestos is mixed in with builders’ rubble it would have to be stripped out, which would involve putting people in to do it, whereas the key principle is to disturb it is little as possible.’

Asked what was being done with asbestos recently removed from Plémont and currently being unearthed at the Esplanade, Mr Fauvel said a new ‘reception cell’ at La Collette was expected to be up and running by next month.

Asked whether anything could be built on the site of the buried asbestos, he said that this was unlikely.

‘Clearly for a building you need a very solid base.

Of the cases brought to court in Jersey over the past five years under Health and Safety Legislation …

- 25 were accidents or incidents

- 31 duty holders were prosecuted

- 18 were related to construction

- 6 were related to building refurbishments

‘We envisage the asbestos to be above the sea water level at the bottom of the pits with ash pits on top of that,’ he said.

However, the Environment Department will have to take into account that the area of coastline from the tanker berth at the Harbour to the tip of Gorey Pier has been designated by the States as a United Nations Ramsar Wetland of International Importance.

Campaigners have expressed concern for some years that the landfill at La Collette – which contains metals – poses a pollution threat to the surrounding waters.

David Cabeldu, spokesman for environmental campaigners Save Our Shoreline Jersey, said: ‘Asbestos is mostly safe once buried and will not leach into the water table.

‘But it is mixed in with boiler parts and other builders’ waste – including immersion heaters and pipes – and will be a nightmare to separate if, indeed, it can be done.’

Mr Cabeldu said that Save Our Shoreline had been in favour of an ‘engineered solution’, preferably turning the substance into glass.

‘TTS were on board with it until the last elections, but the new ministers have different priorities,’ he said.

‘How much longer can we bury hazardous waste at La Collette?

‘We are hoping that DEFRA will have a change of heart, but we aren’t holding our breath.’

Asbestos is a material which was widely used in the Island up until 2000. Although since banned from import or export, it is known to be present in all kinds of buildings. But just how dangerous is this substance, and what should we do if we come across it?

What exactly is asbestos?

Asbestos minerals have been in use since Roman times and are found in several global areas, including Canada, Australia, Russia, China and Brazil. During the Industrial Revolution the substance was widely mined, but it wasn’t until 1924 that the first case of asbestosis was identified in Britain.

Health and Safety director Tammy Fage said: ‘In its heyday it was a remarkable product, particularly for insulation and fire resistance. Unfortunately, no one realised that it was a carcinogen.’

Three main types have been used by the construction industry: chrysotile (white), amosite (brown) and crocidolite (blue).

‘All three are dangerous,’ said Mrs Fage, explaining that the risk is greater from materials in which the fibres are not densely packed together, or in technical terms ‘friable’.

‘Loose installation, like pipe lagging, is the most dangerous. Insulation board, which is soft and easy to snap, is intermediate but still high risk. Then there are materials such as well-bound cement, roof sheets, downpipes, vinyl floor tiles, rubberoid roofing. Often, you can’t tell by looking that it is asbestos.’

What is the risk?

According to Health and Safety, the danger arises if the material is damaged, because then the fibres become airborne and can be inhaled. Any dust released during handling will contain asbestos fibres.

‘We don’t want to be scaremongering,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘If the asbestos is intact and in good condition, it is not a problem.’

However, the statistics are not encouraging. In the UK, asbestos is the biggest occupation-related killer, responsible for more than 5,000 deaths annually. Considering that in 2012 there were 1,754 deaths on UK roads, the risk is clearly not insignificant.

Workers who may be in greatest danger nowadays are construction workers dealing with demolition or refurbishments – carpenters, plumbers, electricians and cable layers, whereas in the 1970s, 80s and 90s cases were more likely to involve shipbuilders, miners and even women making gasmasks during the Second World War.

‘The problem is that whereas road accidents are visible and obvious, respiratory disease can take from 15 to 40 years to develop – and then it is too late,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘The more exposure, the higher the risk. If you are a smoker, you are 20 times more likely to be affected.’

There is no known cure. In the UK, there is a mandatory requirement to report asbestos-related disease, and if someone can show that their ill-health is a direct result of their working situation, there is an industrial injuries compensation scheme.

In Jersey, it appears that there is no requirement to report such cases, and the recourse for individuals is through employers’ liability insurance, but only if they can show a clear link.

Where can asbestos be found?

The answer is in most buildings all around the Island, including older properties. A prime example is the former holiday camp at Plémont.

Health and Safety say they have no evidence to suggest that shiploads of asbestos were imported into Jersey after it had been banned in the UK – although there is a widespread belief that this is the case. However, Mrs Fage said that there was no doubt that a lot of the material was imported over a period of time.

‘If the premises were built before 2000, assume that asbestos is there,’ she said. ‘There is still a lot around in States buildings, schools, hotels and private households, often in garage ceilings or behind chimneys.

Last year there were 102 separate notifications by licensed contractors to remove asbestos from properties in the Island, which is some indication of the scale of the problem.

‘Anyone who works in construction should have awareness training so that they know exactly what asbestos is, where to find it, what to do if they suspect it or if it has been disturbed.’

What does the law say?

Every workplace building should have an asbestos management plan and a management survey. If construction work is undertaken, a demolition / refurbishment survey is required to make sure that asbestos is identified and dealt with in advance.

Most importantly, says Mrs Fage, contractors must ask for the survey. ‘The first prosecution we carried out years ago was a major Island hotel. They had a survey, but the contractor did not think to ask and the hotel did not pass it on. A similar thing happened on States premises, and both the States and the contractor were fined.’

Of the six cases involving asbestos brought to court over the past five years, all have occurred inadvertently during refurbishment work, and in all cases the contractors failed to ensure that a survey had been carried out before starting work.

‘We find it frustrating and disappointing that we keep having to prosecute, but it is difficult to know what else we can do,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘The industry has to take it on board.’

The level of fine is unlimited, but for any business the publicity associated with the court case is more damaging.

How should asbestos be disposed of?

Health and Safety make a clear distinction between the legal requirements, depending on the type of asbestos.

The ‘friable’, most dangerous forms can only be removed by a contractor licensed by the Social Security Minister. The department must be notified of the work 14 days in advance, and Health and Safety review every notification.

For denser material, such as asbestos cement, a license is not required provided the contractor has the approved level of training.

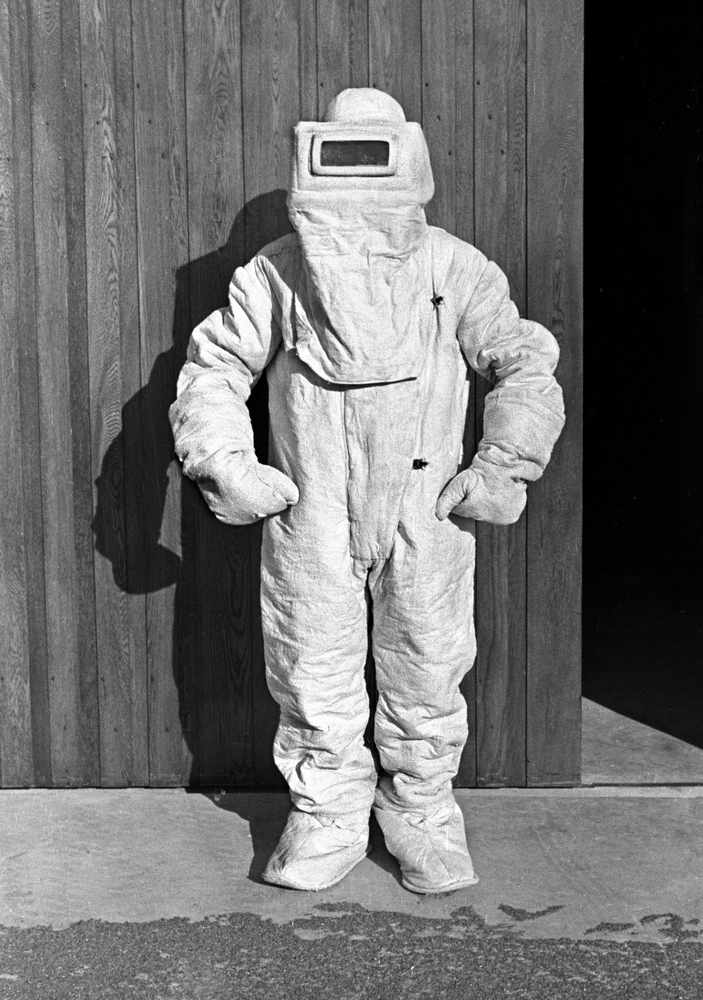

For the average householder wanting to renovate their home, the discovery and disposal of asbestos can be an expensive and time-consuming business, involving safety suits and pressured tents to keep any fibres in. ‘There is no safe level of exposure,’ said Mrs Fage, adding that the department was always happy to give advice if a home owner is unsure.

In many cases, provided the asbestos is undamaged, it is not necessary or realistic to remove all the material, although it may require sealing.

Ultimately, all the Island’s asbestos ends up in sealed bags in the shipping containers at La Collette. Unfortunately, and despite repeated calls for their disposal over a number of years, Transport and Technical Services have failed to come up with a solution – and whatever is decided is likely to cost millions of pounds.

‘Health and Safety do have oversight, because it is a place of work, and it is very much under active debate,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘It is not a risk – but the material is still there. The hard decision has still to be made.’

Asbestos could be present in any building in Jersey that was built or refurbished before the year 2000. Accordingly, the current law requires employers to prevent the exposure of their employees to asbestos. If this is not reasonably practicable, any exposure should be controlled to the lowest possible level. Before any work with asbestos is carried out, the law requires employers to make an assessment of the likely exposure of employees to asbestos dust. The assessment should include a description of the precautions which must be taken to control the release of asbestos dust. A claim can be brought against a previous employer for breach of the law in the event of asbestos disease. However, if the exposure to asbestos occurred before the implementation of the legislation, it would still be possible to claim for some types of asbestos disease under the common law. An employer is under a common law duty to take reasonable care of its employees’ health and safety in the course of their employment. A breach of this duty can give rise to liability quite apart from any need to show a breach of the legislation. If asbestos dust was breathed in in the course of employment, no proper protection was provided, and the employee later develops an asbestos disease as a result of this exposure, it is probable that an employer will be found in breach of the law. This will be the case even if the exposure occurred many years ago. The law does not require asbestos disease victims to identify every employer who exposed them to asbestos. It is highly likely that any job which made a significant contribution to the total amount of asbestos dust inhaled could have led to the development of a disease. Consequently, identifying just one employer which has broken its common law or statutory duties will probably suffice to meet the standard of proof required to sustain a right to compensation.