Swimmers off the north coast had a nasty and painful surprise last week when they found they were sharing the water with hundreds of jellyfish. But what exactly are these visitors, why are there so many this year and for how long will they be disrupting our swims?

EVERY summer, a swimmer, kayaker, surfer or other sea-going Islander or tourist is likely to have a close encounter with a jellyfish.

Usually, however, they are the type whose sting is hardly noticed. And they are usually relatively few and far between.

But this year things have been rather different. During the last few weeks, several swimmers in Bouley Bay have been stung, with some being left with an extremely painful rash and a fear of returning to the sea this summer.

- The largest recorded jellyfish is a lions mane found washed up in Massachusetts Bay in 1870. Its bell (body) was 7 ft wide and its tentacles were over 120 ft long

Initially it was thought the culprits were nettlefish (also known as sea nettles) – a stinging jellyfish more at home off the east coast of the USA than the waters of the English Channel.

And the concern was so great that the Health Department took the unusual step of warning people to take extra care in the water, and urged parents not to let their little ones try to touch any of the creatures washed up on the beach.

Now, however, it is believed the creatures were mauve stingers – a relatively uncommon jellyfish which, as anyone who has come into contact with them will confirm, lives up to its name.

It is believed this year’s unusual bloom – which has seen hundreds occupy the waters in Bouley Bay and other parts of the north coast – was a result of warmer sea temperatures early in the year. This is thought to have produced a strong breeding season, which has resulted in hundreds of mainly juvenile mauve stingers massing in the seas around the Island.

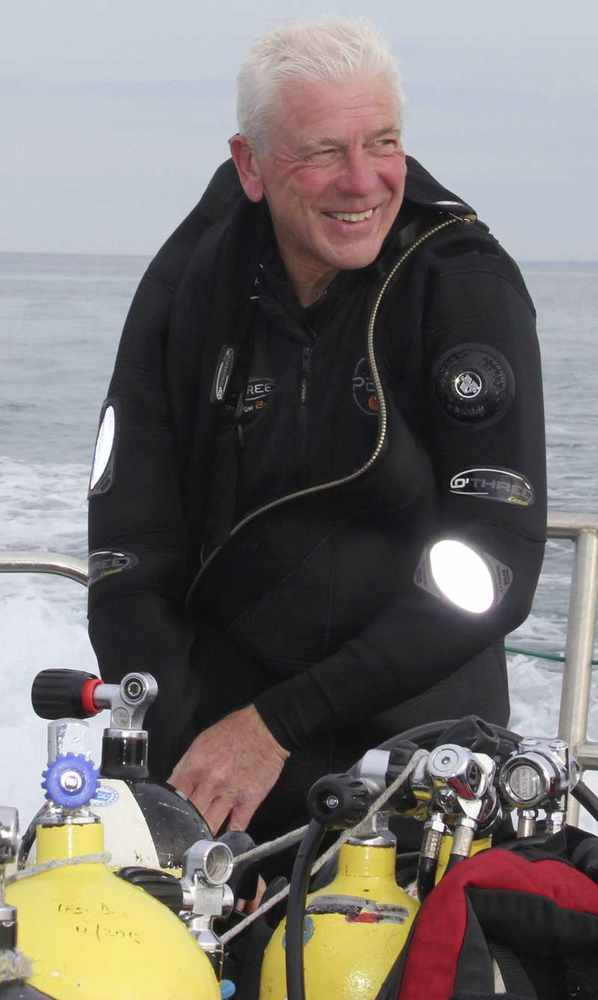

Kevin McIlwee, co-ordinator of Sea Search, a group which records marine life in waters around Jersey, said: ‘The mauve stingers breed in a slightly different way to other jellyfish.

‘The difference is that jellyfish usually breed and produce larvae which drops to the seabed. Once it is ready it goes out on its own and floats up

the water. However, the mauve stinger doesn’t drop its larvae onto the sea bed – they remain high up in the water.

‘So it begs the question, what has been different this year?

‘One of the things we noticed is that the water temperature warmed up a bit more rapidly than usual around April and May. It doesn’t take much – just 1°C or 2°C more than usual can make a big difference and increase the amount of food in the waters and therefore increase their presence.’

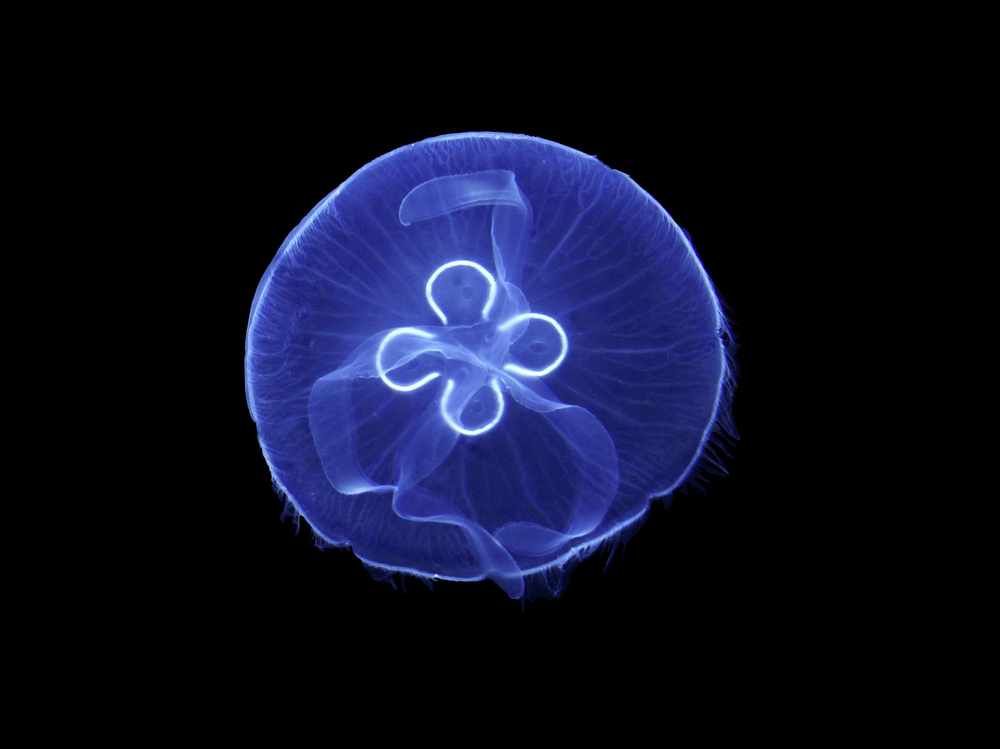

While jellyfish blooms are not unusual, it is usually the harmless barrel and moon jellyfish that are most commonly seen in Channel Islands waters. But when a sudden increase happens, the resident jellyfish can stay for longer than many would like, mainly thanks to the strong tidal currents around the Island.

- Most jellyfish stings are so minor they do not require pain relief. However, people coming into contact with a severe stinger such as a lions mane may need to take action.

- Anyone who watched US sitcom Friends in the 1990s when Monica was stung and called upon Joey and Chandler for help will tell you that dousing the affected area in urine is the best way to ease the pain. However, this (and vinegar) is no longer recommended, as it could aggravate unfired stinging cells.

- Other previously recommended substances, such as baking powder and alcohol, should also be avoided. Instead, remove the tentacles with tweezers or a clean stick and apply an ice pack. Use a razor blade, credit card or shell to remove any poisonous sacs that are stuck to the skin. It may help to apply a small amount of shaving cream to the affected area first. If the pain is severe, phone 999

‘The unique thing about the north coast is that you get these eddies – particularly at Grève de Lecq, Bonne Nuit and Bouley Bay – and these jellyfish come in on these currents and because of the cyclical flow in the bays they just go round and round,’ said Mr McIlwee.

Many jellyfish can propel themselves through the water, but can do little to counter Jersey’s strong currents, so it is unclear for how long the mass of mauves will remain in our seas.

However, experts believe that jellyfish numbers are likely to peak in the next few weeks, before steadily declining through the rest of the summer and autumn.

Although they can cause a nasty rash, mauve stingers are not the most dangerous jellyfish in Jersey’s sea.

The brightly coloured lion’s mane jellyfish – the biggest recorded species of jellyfish in the world – occasionally visit our waters, and these easily out-sting the mauves. And just a few weeks ago during a dive at Bouley Bay, Mr McIlwee photographed a lion’s mane doing its best to resolve the mauve stinger problem – by eating one

of them.

- In March of last year we experienced another uninvited guest to the Jersey seas, in the shape of the large barrel jellyfish. The Rhizostoma pulmo has been recorded from Essex throughout the English Channel and Irish Sea and the coast of Ireland, the Outer Hebrides and the North West coast of Scotland. It has a solid appearance and varies in colour from whitish pale or yellow to shades of green, blue, pink or brown. Barrels are the basking sharks of the jellyfish world, despite their size they feed only on plankton and their sting is not powerful enough to harm humans.

- In August we then experienced another influx of beautiful yet painful species of jellyfish, the Chrysaora hysoscella is a common jellyfish. The compass jellyfish has a saucer-shaped bell, with 32 semi-circular lobes around the fringe, each one with a brown spot. On the upper surface of the bell, 16 brown V-shaped marks radiate outwards from a dark central spot. The stinging cells and venom of this particular jellyfish are strong and can be very painful, however if you keep your distance youll be safe from a sting.