- 75 years to the day since Jersey was occupied by Nazis forces

- Hundreds of enemy soldiers came ashore on 2 July 1940 and orders come into force

- Islanders were issued an ultimatum outlining the punishments for resistance

- Read some early Occupation recollections below

SEVENTY-FIVE years ago today Islanders woke to their first day under German occupation as hundreds of enemy soldiers came ashore.

The punishment for resistance, made clear in an ultimatum received the previous day, would have been ‘heavy bombardment’ of the Island.

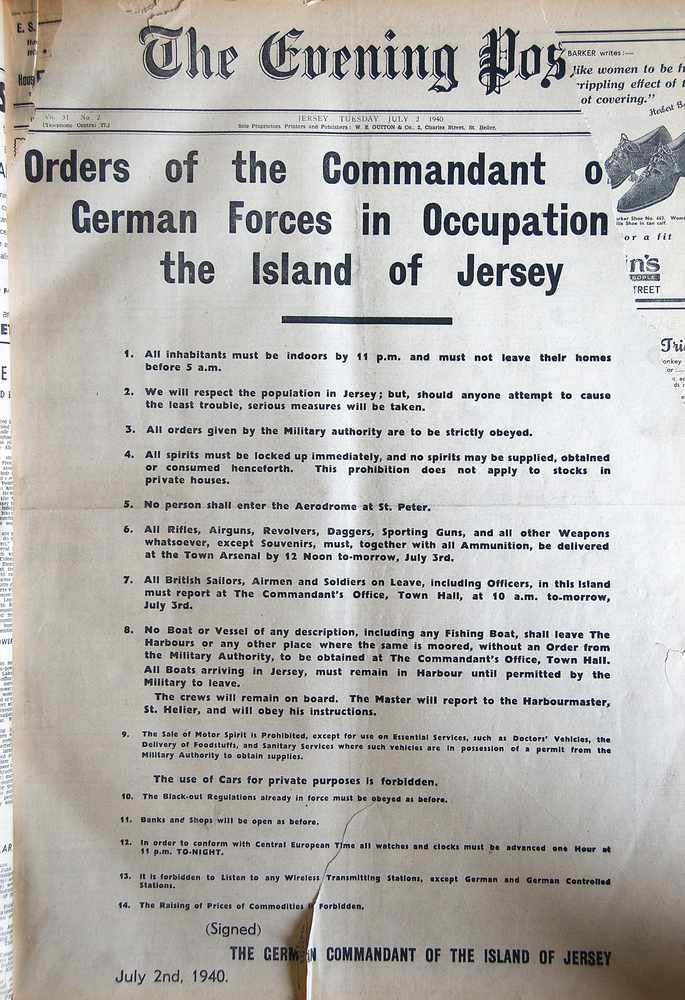

The front page of the Evening Post of Tuesday 2 July 1940 was entirely taken up with the orders of the Commandant of German Forces in Occupation of the Island of Jersey.

These included prohibition of the sale of alcohol and petrol, moving clocks forward one hour to central European time and outlawing radios.

June 1940 had been a month of chaos and uncertainty as the Germans blitzkreiged through France and ever closer to the Channel Islands.

On 17 June the decision was made by the British government not to defend Jersey and all troops and military equipment were to be removed and civilians who wanted to leave were told to register.

Of the 23,000 who did only around 6,500 got away to the UK.

As they could only take what they could carry they had to leave possessions, cars and pets behind and many homes were ransacked.

Throughout the last weeks of June, the States sat in special sittings, sometimes in camera, but mostly before a packed public gallery, preparing for Occupation, while potatoes were still being exported and adverts in the EP proclaimed business as usual.

On the evening of the 28th, bombs were dropped on the Harbour area and at La Rocque, killing nine and injuring ten.

At 9 pm the Home Office issued a declaration that Jersey was a demilitarised zone and all military personnel and material had been removed.

On 1 July communication with the UK ceased and the States met at noon to consider the German demand to surrender or face the consequences – but they had no choice but to acquiesce.

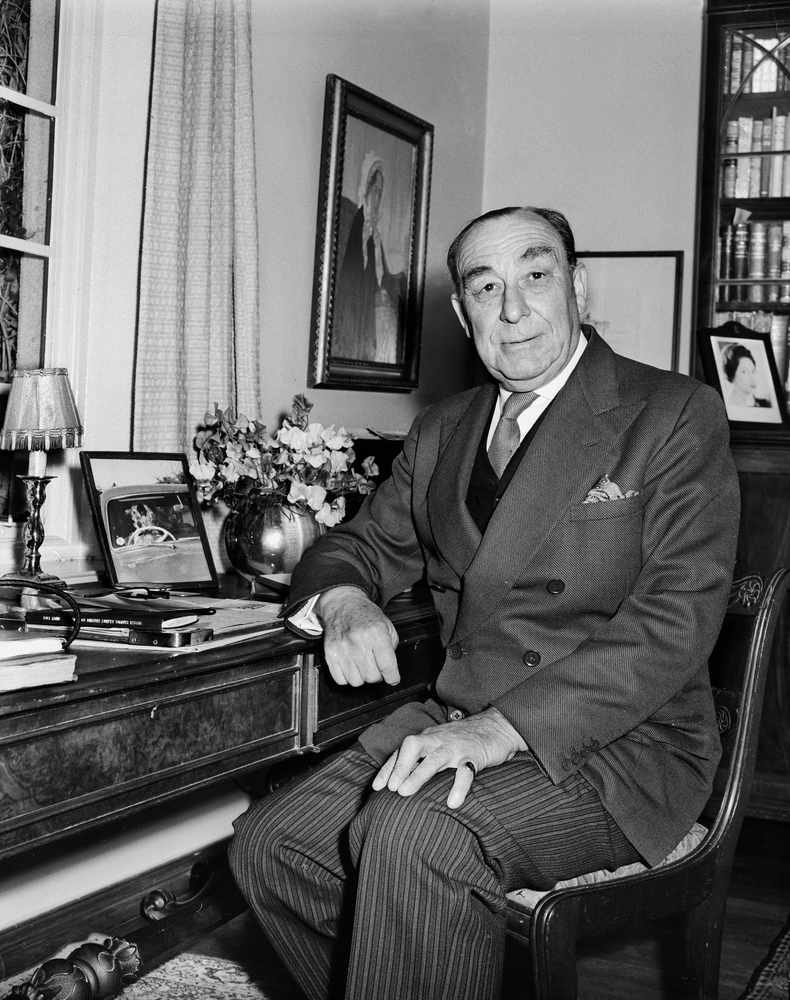

Immediately afterwards, the Bailiff, Alexander Coutanche, addressed the crowd in the Royal Square to announce the Island’s surrender and the impending arrival of German forces.

About 100 arrived later in the day as, according to the ultimatum, white crosses were painted at prominent locations – at the Airport, Harbour and in the Royal Square – and white flags were draped from all buildings.

Before going to the Airport to meet the first German officers, and set in process their orders for occupation, Mr Coutanche lowered the Union Flag at Fort Regent.

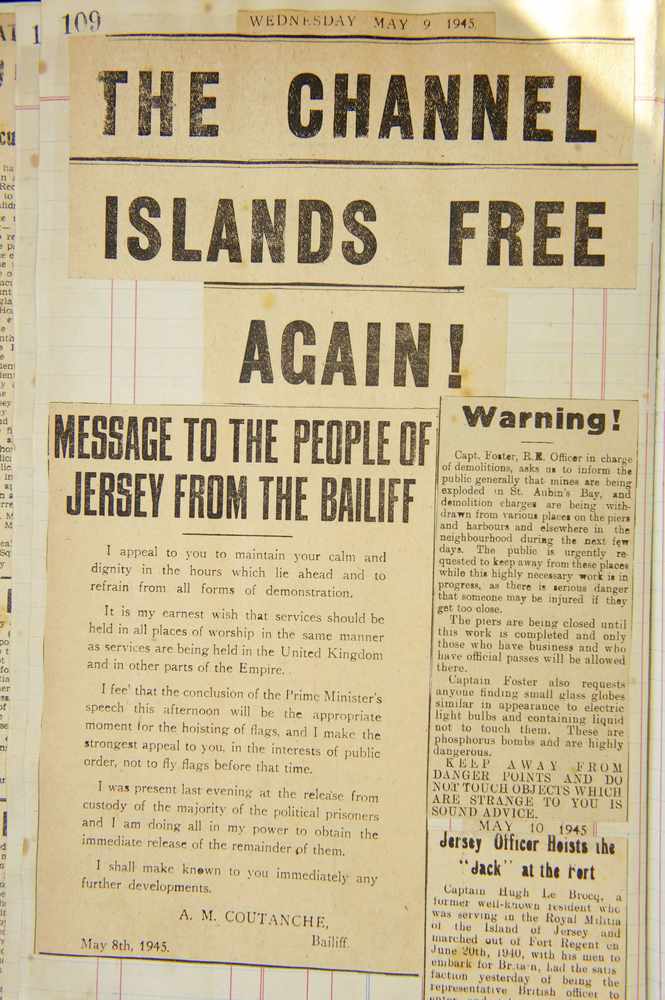

It would not be hoisted again until 9 May 1945.

THE British are often accused of being fixated with the Second World War, and the same could be said of Jersey, which, since the 50th anniversary in 1995, places great emphasis in celebrating the Island’s Liberation in 1945. Seventy years on, Liberation Day is a joyous occasion, the marking of which ignites deep passions in those who lived through the Occupation, were evacuated, interned, fought for their country or lost loved ones.

But in putting so much effort into celebrating the Island’s freedom, the price paid by Islanders – mostly volunteers – in the First World War has been overlooked in telling the story of Jersey in the 20th century.

Another significant date that passes by without official recognition is the anniversary of the Occupation on 1 July, when Jersey surrendered to German demands, and the following day, when Islanders began life under the Nazi yoke. In homes around the Island today, memories will be stirred, horrors recalled and long-gone friends and loved ones will be remembered.

The first days of July may be the darkest in our history, but that is no reason to forget them.

In The German Occupation of Jersey, Occupation diarist Leslie Sinel recorded for 2 July 1940: ‘The white flags of surrender can now be pulled down, but the swastika flies over Fort Regent!

‘The Germans appear anxious to maintain the social life of the Island, and have issued late passes to persons working at dance halls, etc.

‘One man was stopped by a zealous German patrol and promptly arrested when the name on his pass was read as ‘Churchill’!

In his memoirs, Alexander Coutanche, recalled the surrender.

At home, on the evening of 1 July, he received a surprise visit from the Island’s first commandant, Captain Gussek, and his retinue who were anxious to complete their paperwork.

Having changed into scruffy gardening clothes, including trousers torn at one knee, the Bailiff’s attire did not impress the Germans gathered in his drawing room.

‘It was made clear to me who was in charge of the whole operation when he introduced himself to me as Captain Gussek.

‘His method of expressing some surprise at my appearance was to put a monocle into his right eye, the better to take me in in those days.

‘I used on occasion to wear a monocle myself and it so happened that it was in the pocket of my jacket now I was able to repay the compliment and I did so.

‘We took good stock of each other’.

Pam Tanguy has a vivid memory of the bombing of La Rocque Harbour, even though she was only four; as she says being shot at is something you never forget.

Mrs Tanguy recalls being in a field (now an estate of houses) close to the harbour on a very hot Sunday evening, where her parents were working.

Just as she was about to open the packet of salt that came in a bag of crisps there was a big explosion.

‘Three big shapes came trailing along, Heinkel bombers they were, and they started firing at us and my father said “get down, get down”!’ she said.

‘We were lying flat in the rows of tomatoes until they flew away.’

They rushed home to the seaside cottage where she lives today and she and her mother hid in the cupboard under the stairs.

Her father went to La Rocque where he discovered the bodies of three men who had died from shrapnel wounds.

Occupation news scrapbook available online

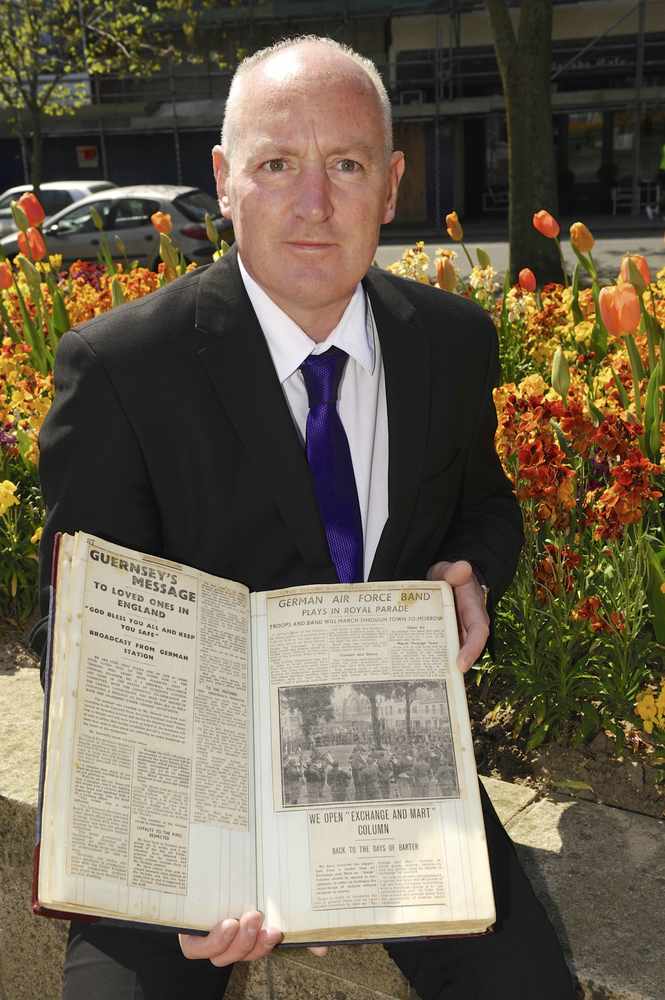

EARLIER this year, a wartime scrapbook was put online to show how the news was delivered to Islanders when the Germans occupied Jersey.

The 197-page volume contains hundreds of cuttings of articles from the Evening Post – the former name of this newspaper – published between July 1940 and June 1945.

The book, called the William Brown Ledger, was recently donated to the Channel Islands Occupation Society by Mr Brown’s son, Roger, who still lives in the Island.

It begins with a message from the paper about Britain’s decision to leave the Channel Islands undefended in 1940 and ends five years later with cuttings from a special Liberation Day picture supplement that also covered the subsequent visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

The book can be viewed for free here

CIOS archivist Colin Isherwood said: ‘The book covers the very, very early days of the decision to evacuate, the first bombings, rationing and on to the Liberation and all sorts in between.

‘It was put together by Mr Brown, who was a policeman during the Occupation, and his son contacted me to ask if we would like it for the society.

‘It contains quite a few order papers and proclamations from the Occupation as well.’

According to Mr Isherwood, Mr Brown was summoned by the German authorities who asked him why he was documenting the news in a scrap book.

That order was signed by Baron Von Aufsess – the German’s chief administrator for the Channel Islands – who kept and published a diary of his time in Jersey.

Ultimately, the occupying forces allowed Mr Brown to continue documenting the news.

Mr Isherwood added: ‘The whole story behind the paperwork is superb. The book is in beautiful condition and has been well looked after.

‘The Germans allowed Mr Brown to keep his book after he said it was just a record of public information.

‘It’s an unusual piece. I’ve seen diaries, but not a scrapbook of newspaper cuttings.’

The original scrapbook is due to be displayed at St Mary’s Parish Hall when the CIOS hold a week-long event to show their collections between 4 and 10 May.

The first cutting in the scrapbook is a small news story and message from the JEP about Britain’s decision not to defend the Channel Islands.

It said: ‘A decision of the most vital importance to the Island was taken today by the British Cabinet and announced to the States of Jersey this afternoon by His Excellency the Lieut-Governor.

‘This Island is not to be defended; it is to be completely demilitarised and declared an undefended zone.

‘The reasons governing this decision are the concern of His Majesty’s Government, and we may rest assured that the most profound attention was given to every aspect before it was decided to take this step.

‘We believe there to be no reason at all for panic; the government of the Island will go on, and everything will be done to ensure the smooth working of the administration. Keep calm, obey the regulations issued by the authorities and carry on, as far as it is possible, with one’s ordinary business.

‘We believe we can offer no sounder or saner advice.’

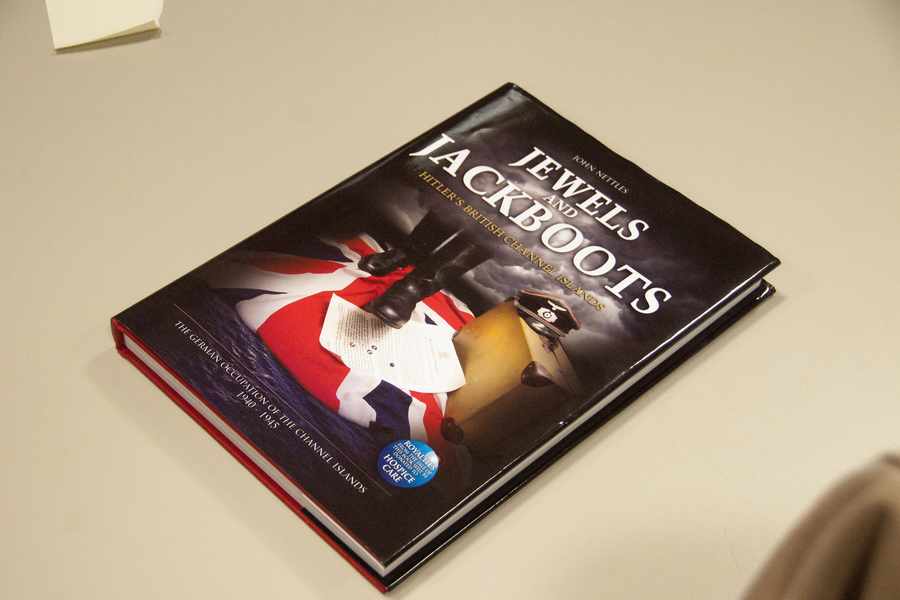

In 2012, the JEP reviewed John Nettles new book about the Occupation, Jewels and Jackboots:

EVER since John Nettles helped bring Jersey into the homes of millions during his stint as DS Jim Bergerac, the Island has held him in great affection.

That fondness is reciprocated and gave him an important feeling for the community which informed the way he approached his work.

However, Mr Nettles, a university history scholar, embarked on his research and the writing of the book with great emphasis on providing an objective account of the Channel Islands Occupation experience.

As a result, Jewels Jackboots paints a very fair picture which does not shy away from some of the more difficult aspects of those five awful years.

In a chapter entitled Precious Little Resistance, the author looks at the lack of armed resistance in the Island.

‘Was there not a small army of men and women ready and willing to lay down their lives in the cause of freedom from the Nazi yoke?’ he asks, before going on to explain that the conditions necessary to allow such a movement, not least a place of refuge where fighters could hide out, were absent in Jersey and the other islands.

Instead, the islands’ leaders presided over a cautious balancing act based on an understanding that they would co-operate if the Germans visited no violence on the civilian population.

Mr Nettles praises the diplomacy of those leaders and the service they did for their islands. The chapter gives many personal accounts of Occupation life and concludes that this was necessary and reasonable co-operation, not collaboration.

Mr Nettles has a special interest in the treatment of the Jews in Jersey and devotes a chapter to the subject.

He concludes that the islands’ authorities governed with little or no regard to the interests of the Jews, whose plight in Europe he says they must have known.

‘They didn’t even try,’ he writes. ‘Indeed the opposite appears to be the case, for by registering anti-Jewish measures in the Royal Courts without demur and by helping to implement those measures, the Jews were actually deprived of any interests or rights of citizenship at all.

The Island government actively helped and connived in a process designed to reduce them to non-persons with no legitimate interests of any kind.’

Jewels and Jackboots combines an authoritative narrative with personal accounts and pictures which bring the story alive. Those pictures often lack captions which would

make the book a more enjoyable thing to read and flick through, and there are points where the author has assumed the reader will know the context and importance of documents without explanation.

There is, however, a very useful timeline at the start of the book which helps the reader quickly place individual incidents within a broader context.

It is a coffee-table style book with academic credibility. Many, many months of research, both interviews with those who lived through the Occupation and through the study of written archive material, have been condensed into a history which is an important addition to the literature on one of the darkest periods of Jersey’s past.

It manages to tell two stories – that of the clash of countries and ideologies alongside that of the experience of ordinary people trying to get on with life amid the tumult.