Alan Harold Buchanan, a qualified naval architect and aeronautical engineer who worked as a draftsman on bombers and flying boats during the war, moved with his family to the Island in the late 1960s, by which time his name for exceptional craftsmanship and design of fast, seaworthy and beautiful yachts was legendary.

Born on 20 October 1922, the first of three sons to Harold, he showed a great interest in the sea from an early age and spent much of his youth messing around in boats at West Mersea in Essex, where the family had a small holiday cottage.

He was aged 17 when the Second World War began and, after he gained qualifications in naval architecture and aeronautical engineering, he became a wartime draftsman and project engineer for aircraft manufacturers Handley Page and Shorts, working on Halifax and Sterling bombers and Sunderland flying boats.

This also included an involvement in the Barnes Wallace’s bouncing-bomb project. In the later war years he had to go round the aerodromes in the UK advising fitters on how to repair damaged aircraft that had made it back from bombing raids.

He would recount these experiences with a slight degree of regret and irritation, as he was not allowed to fulfil his real ambition, which was to join the Royal Navy and see active service, because he was in a reserved occupation.

Once the war had ended he left Handley Page and set up his own yacht design business, which quickly moved to the east coast yachting mecca of Burnham-on-Crouch. There it thrived and he soon became one of the most prolific and well-respected ocean racing yacht designers of his time.

Yachts which he designed won the prestigious Sydney-to-Hobart race in the 60s, numerous Cowes Week events, the Fastnet race and Admiral’s Cup, as well as the East Anglian Offshore Championship on no fewer than ten occasions.

Alan was also a successful yachtsman himself, winning many honours, crossing the Atlantic twice and competing in the Sydney–Hobart race and two Fastnet races.

He married Pat in London in the early 1950s and the couple had two children, Richard and Andrew. They can recall their home in Essex being full of guests who had come down from London to race at the weekend, and also many happy sailing experiences with their father both in Burnham-on-Crouch and in Jersey. There was great excitement, too, at the launches of his many designs and at the sea trials of yachts that went on to achieve success.

The family moved to Jersey in 1969 with five of their staff at a time when yachting facilities in the Island were minimal. The States were delighted to welcome a renowned naval architect and marine surveyor, one who, in 1965, had designed a 40-ft masthead sloop called Kalina for Clem Challinor, a Jersey Deputy and keen racing yachtsman.

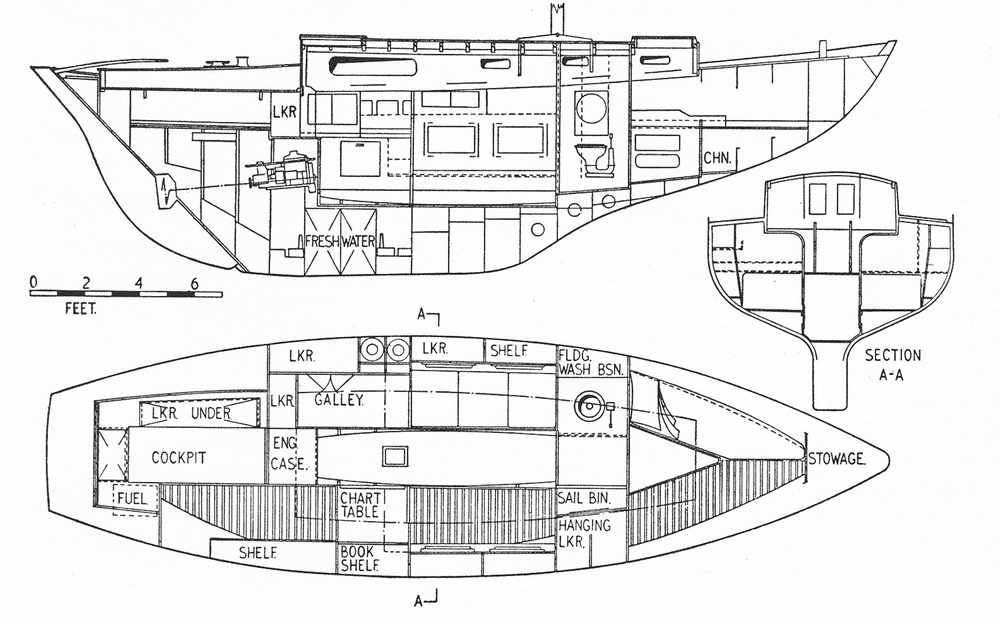

Alan continued to design at his farmhouse studio in St Mary, although the emphasis shifted away from racing yachts to cruising designs, with such designs as the CI 22 and 32 flowing off his drawing board. He also was heavily involved with the local marine industry, as he started to do a great deal of survey work, which he carried on into his very late 70s.

He gave a lot of time to the Maritime Museum and was involved in the restoration of the Fiona, a traditionally built fishing boat. One of his last projects was to work on the restoration of a Carteret smack, the Neuve Maive.

He produced more than 2,400 designs, from which up to 2,000 boats were built, and these drawings have been donated by his family to the National Maritime Museum Cornwall. His work and contribution to the marine industry was recognised by a fellowship of the Royal Institution of Naval architects and the award of the institution’s Small Craft Group medal in 1996.

As well as being passionate about the sea, Alan was a great animal lover, especially horses, and he was an accomplished dressage rider and a keen member of the Jersey Drag hunt. He hunted well into his 70s.

The most abiding of his qualities was his incredible enthusiasm for whatever he did and his ability to communicate this to those around him, including his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He always had time to offer advice and help to anyone who asked or needed it, and for this alone he will be sorely missed.

Sadly, his wife died in 1994, a loss from which he never fully recovered. He leaves two sons, Richard and Andrew, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, to whom the JEP extends sympathy.