Consideration was given to using the subterranean network by the department, which is responsible for the Island’s stock of redundant asbestos that is currently being stored in old shipping containers at La Collette.

Sound insulation infill

Thermal insulation lagging

Felts, blankets, mattresses, tape, rope

Asbestos boards

Gaskets, washers, drive belts, conveyor belts

Roofing sheets and slates

Drain and flue pipes

Fascia boards, bath panels, ceiling tiles, toilet seats, cisterns

Damp proof courses, PVC panels and cladding

Lab bench tops, extraction hoods, fume cupboards

Brakes and clutches

However, after drawing up a shortlist of seven potential plans, which included ‘entombing the asbestos in the redundant German Occupation tunnels’, authorities decided that the most sensible move would be to store the waste material at La Collette in a specially designed asbestos pit.

TTS has now submitted a planning application to use the pit, a five-metre deep hole that covers an area of about 12 tennis courts, which has been created on reclaimed land at the back of the site, as a permanent storage site.

It comes after the previous Environment Minister, former Deputy Rob Duhamel, fought to use the site as a ‘temporary’ storage space while he investigated other methods of dealing with asbestos, such as a super-heat treatment known as vitrification that turns the waste into an inert glass-like substance.

The pit is close to where the asbestos is currently being stored and Transport Minister Eddie Noel said that storing the material in a safer structure at La Collette represented the best way forward.

Other disposal methods included encasing the asbestos in concrete in its current location, relocating the containers and injecting them with concrete grout, exporting the waste to the UK, exporting it for vitrification, or leaving it in place in shipping containers.

‘The only realistic option is to bury it in secure pits on a permanent basis.

‘We certainly don’t want to have to move it twice. We want to do it once and do it right.’

Deputy Noel added that his department would start moving the waste as quickly as possible, presuming planning permission was granted.

He explained that the process raised a number of technical issues such as sorting and rebagging the material where necessary and transporting it safely.

When asked about the possibility of using super-heat treatment on the hazardous material, Deputy Noel said that such a move was not feasible at the moment, but that it could be a possibility in the future as the process and technology developed.

Asbestos is a material which was widely used in the Island up until 2000. Although since banned from import or export, it is known to be present in all kinds of buildings. But just how dangerous is this substance, and what should we do if we come across it?

What exactly is asbestos?

Asbestos minerals have been in use since Roman times and are found in several global areas, including Canada, Australia, Russia, China and Brazil. During the Industrial Revolution the substance was widely mined, but it wasn’t until 1924 that the first case of asbestosis was identified in Britain.

Health and Safety director Tammy Fage said: ‘In its heyday it was a remarkable product, particularly for insulation and fire resistance. Unfortunately, no one realised that it was a carcinogen.’

Three main types have been used by the construction industry: chrysotile (white), amosite (brown) and crocidolite (blue).

‘All three are dangerous,’ said Mrs Fage, explaining that the risk is greater from materials in which the fibres are not densely packed together, or in technical terms ‘friable’.

‘Loose installation, like pipe lagging, is the most dangerous. Insulation board, which is soft and easy to snap, is intermediate but still high risk. Then there are materials such as well-bound cement, roof sheets, downpipes, vinyl floor tiles, rubberoid roofing. Often, you can’t tell by looking that it is asbestos.’

What is the risk?

According to Health and Safety, the danger arises if the material is damaged, because then the fibres become airborne and can be inhaled. Any dust released during handling will contain asbestos fibres.

‘We don’t want to be scaremongering,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘If the asbestos is intact and in good condition, it is not a problem.’

However, the statistics are not encouraging. In the UK, asbestos is the biggest occupation-related killer, responsible for more than 5,000 deaths annually. Considering that in 2012 there were 1,754 deaths on UK roads, the risk is clearly not insignificant.

Workers who may be in greatest danger nowadays are construction workers dealing with demolition or refurbishments – carpenters, plumbers, electricians and cable layers, whereas in the 1970s, 80s and 90s cases were more likely to involve shipbuilders, miners and even women making gasmasks during the Second World War.

‘The problem is that whereas road accidents are visible and obvious, respiratory disease can take from 15 to 40 years to develop – and then it is too late,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘The more exposure, the higher the risk. If you are a smoker, you are 20 times more likely to be affected.’

There is no known cure. In the UK, there is a mandatory requirement to report asbestos-related disease, and if someone can show that their ill-health is a direct result of their working situation, there is an industrial injuries compensation scheme.

In Jersey, it appears that there is no requirement to report such cases, and the recourse for individuals is through employers’ liability insurance, but only if they can show a clear link.

Of the cases brought to court in Jersey over the past five years under Health and Safety Legislation …

- 25 were accidents or incidents

- 31 duty holders were prosecuted

- 18 were related to construction

- 6 were related to building refurbishments

Where can asbestos be found?

The answer is in most buildings all around the Island, including older properties. A prime example is the former holiday camp at Plémont.

Health and Safety say they have no evidence to suggest that shiploads of asbestos were imported into Jersey after it had been banned in the UK – although there is a widespread belief that this is the case. However, Mrs Fage said that there was no doubt that a lot of the material was imported over a period of time.

‘If the premises were built before 2000, assume that asbestos is there,’ she said. ‘There is still a lot around in States buildings, schools, hotels and private households, often in garage ceilings or behind chimneys.

Last year there were 102 separate notifications by licensed contractors to remove asbestos from properties in the Island, which is some indication of the scale of the problem.

‘Anyone who works in construction should have awareness training so that they know exactly what asbestos is, where to find it, what to do if they suspect it or if it has been disturbed.’

What does the law say?

Every workplace building should have an asbestos management plan and a management survey. If construction work is undertaken, a demolition / refurbishment survey is required to make sure that asbestos is identified and dealt with in advance.

Most importantly, says Mrs Fage, contractors must ask for the survey. ‘The first prosecution we carried out years ago was a major Island hotel. They had a survey, but the contractor did not think to ask and the hotel did not pass it on. A similar thing happened on States premises, and both the States and the contractor were fined.’

Of the six cases involving asbestos brought to court over the past five years, all have occurred inadvertently during refurbishment work, and in all cases the contractors failed to ensure that a survey had been carried out before starting work.

‘We find it frustrating and disappointing that we keep having to prosecute, but it is difficult to know what else we can do,’ said Mrs Fage. ‘The industry has to take it on board.’

The level of fine is unlimited, but for any business the publicity associated with the court case is more damaging.

How should asbestos be disposed of?

Health and Safety make a clear distinction between the legal requirements, depending on the type of asbestos.

The ‘friable’, most dangerous forms can only be removed by a contractor licensed by the Social Security Minister. The department must be notified of the work 14 days in advance, and Health and Safety review every notification.

For denser material, such as asbestos cement, a license is not required provided the contractor has the approved level of training.

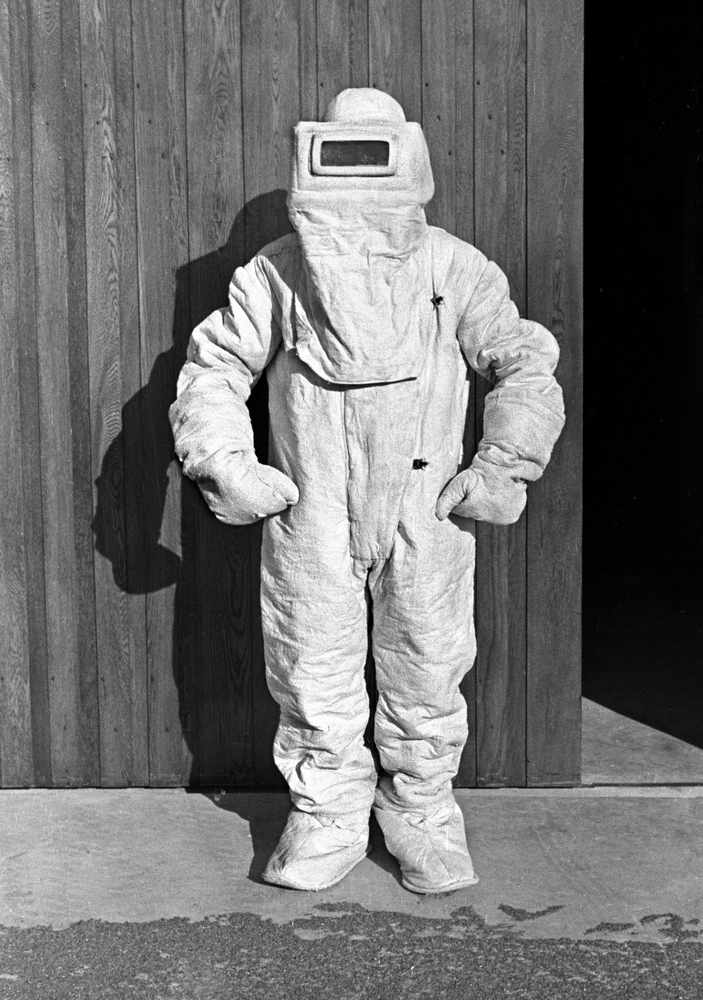

For the average householder wanting to renovate their home, the discovery and disposal of asbestos can be an expensive and time-consuming business, involving safety suits and pressured tents to keep any fibres in. ‘There is no safe level of exposure,’ said Mrs Fage, adding that the department was always happy to give advice if a home owner is unsure.

In many cases, provided the asbestos is undamaged, it is not necessary or realistic to remove all the material, although it may require sealing.

Ultimately, all the Island’s asbestos ends up in sealed bags in the shipping containers at La Collette. Unfortunately, and despite repeated calls for their disposal over a number of years, Transport and Technical Services have failed to come up with a solution – and whatever is decided is likely to cost millions of pounds.

‘Health and Safety do have oversight, because it is a place of work, and it is very much under active debate,’ Mrs Fage said. ‘It is not a risk – but the material is still there. The hard decision has still to be made.’