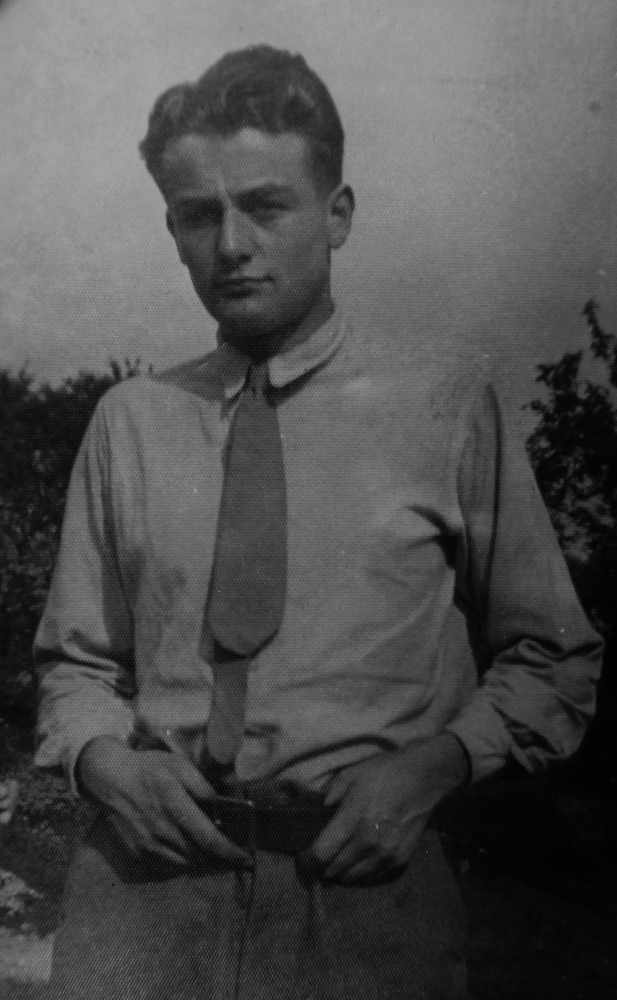

Tristram Colledge spoke to Michael Ginns about his experiences as a teenage prisoner of war:

BETWEEN the ages of 14 and 17, Michael Ginns lived in an 18th century castle in a small town in rural Germany.

Fairytale though it may sound, Michael’s home was topped with barbed wire – and he was one of more than 600 Islanders imprisoned within its walls.

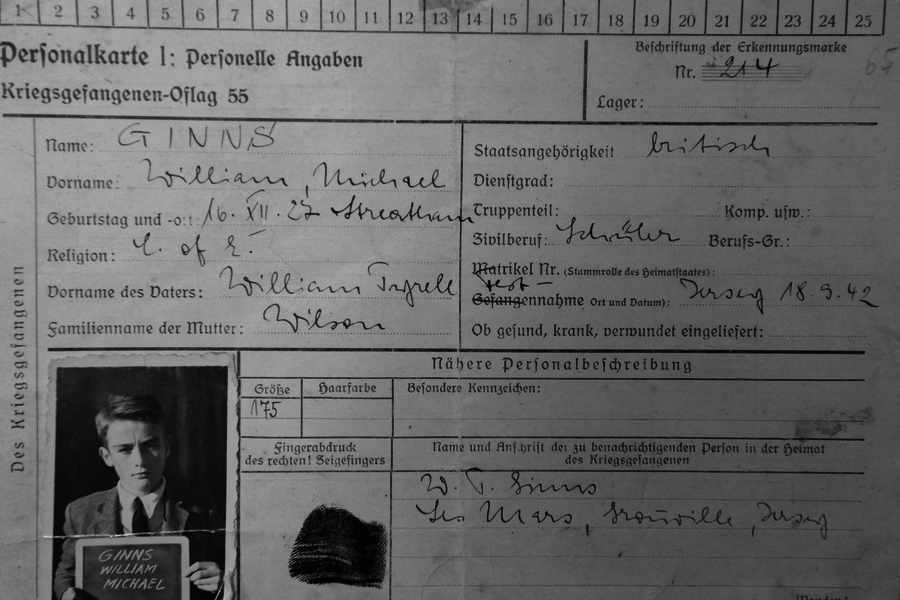

On 15 September 1942 the Ginns’ were among dozens of UK born families living in Jersey to receive a notice ordering their immediate deportation to Germany.

Unlike those less fortunate who had to be ready to leave the following morning, Michael, then a pupil at Victoria College, his mother and his father, were given four days to prepare themselves for the German unknown.

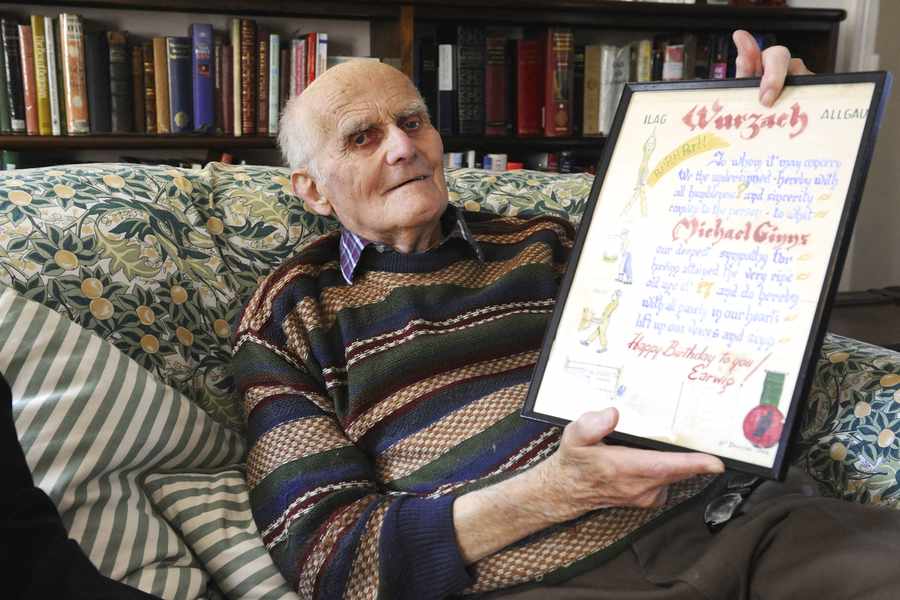

‘We could have been going to a concentration camp, we really had no idea,’ says Michael, now 87, an Occupation history expert and author of several books on the subject, as he speaks from his St Ouen home.

‘There were rumours going around that there were English destroyers waiting out in the Channel to intercept the ships and take us all to England. When we got on the boat I remember a German commander came up to me and said: “On behalf of myself and my comrades we wish to apologise for what is happening to you. It is wrong to make war on civilians – we’ve been in the firing lines in France, we’ve seen it and it is wrong. Please accept my apologies.” I didn’t really acknowledge what he said, but at the age of 14 I suppose I wasn’t as fulsome as I might have been.’

Unfortunately, the rumours did not materialise and the boat was not intercepted by British forces. After crossing the Channel, the large group was then shuffled on board a train for a three day journey through France and Belgium, finally reaching Germany and the Baden-Württemberg town of Bibberach, 20 miles from Bad Wurzach.

‘The only time that we suffered hostility was at Trier. There were passenger trains with people shaking their fists, but we just ignored them. We reached Bibberach at nine o’clock on Sunday morning and we had to march up the hill to the camp. I’ve done it since- it is quite easy, but when you’ve been stuck in a railway coach for three days, it’s a bit more difficult.

‘When the Germans say they didn’t know about Concentration camps I am inclined to believe them because we went past a row of houses and there were German housewives watching on in horror – it seemed to have been the first time that they had seen women and children marched under armed guard.’

Michael spent six weeks at the Bibberach camp – which he says was the most difficult and his most hungry period of time that he spent as a prisoner of war.

‘When we left Bibberach on October 31, it was a miserable afternoon. You can imagine, it was getting dark, we came through the town of Bad Wurzach, in through the gates and we got to the courtyard and there was this enormous building. I thought: ”Oh my God what have we come to”.’

However, despite a daunting start, Michael quickly grew accustomed to life in the Schloss.

‘After six weeks of meagre portions of cabbage soup, it was quite a difference. We had a continuous supply of Red Cross parcels up to Christmas 1944. In the end, we were better off for food there than the people left behind in Jersey.

‘The guards were completely relaxed, they were friendly and they used to exchange cigarettes for some of our soap that came in the parcels.’

And, with the added companionship of school friends, the chance to venture around the town, and the close proximity to teenage girls, things were not all bad, Michael says, with a boyish glint in his eye that belies his years.

‘We had the life of old Riley! It was okay because you had dances once a week, stage shows twice a month, walks in the countryside twice a week, dark corridors and teenage girls.

‘I used to go out into the town with a couple of friends to get the milk for the children, call at the baker’s shop to get white bread for invalids and rolls for the children and any other errands that needed to be done. We soon learned that if you took a bar of soap to a farmer’s wife, she was ecstatic because German didn’t have proper soap – we used to get lots of things given to us.’

Even though life inside the Schloss was more mundane, Michael recalls some very unexpected and unusual happenings.

‘My mother, who was the camp’s nurse, used to see a ghostly hooded figure. The first time she saw it, she thought it was the camp cat, but the next time she saw it somebody died and thereafter whenever any body died, the hooded figure would appear the night before. She learned to expect it because there was always some elderly person in the isolation ward.

‘One night she saw the hooded figure and nobody was ill, but the next day someone slipped on the ice, fractured his skull and died that night. We also had the white lady that used to sit in the room next to ours combing her hair.’

In total, 12 people died while they were interned at Bad Wurzach, but the death that most affected the then teenager, did not occur until soon after he was repatriated in March 1945.

‘We were on board a Red Cross train in Munich and we had stopped at the station. Five or six of us were handing up coal into the carriage and as I was doing it I saw one of my friends, Carl, with a flea brush in his hand. Moments later, I heard him on the roof. There was a flash and a bang – he had forgotten there was a 16,000 volt cable above him. He touched it with his flea brush and he was instantly flung off the roof and killed. That stays with me to this day.’

Because of his early repatriation, Michael did not see the liberation of the camp by French forces – something he says that gave him immense frustration.

Since then though, Michael and his wife Josephine have returned to the town dozens of times and in January 2008 he was the first foreigner to be awarded the Bad Wurzach Citizens Silver Medal of Honour for his reconciliation work that aided in the town being twinned with St Helier a few years earlier.

Michael was also a founding member of the Jersey branch of the Channel Island Occupation Society and as president he played a key part on re-opening a number of the Island’s German bunkers for public viewing.

In 2009, ten years after he first started research, Michael completed Jersey Occupied, The German Armed Forces in Jersey 1940-1945 – his greatest work as a historian.

And although he is used to writing about history, this week, on his return to the small German town, he will revisit his story – a 17-year-old, seventy years on.