Historian Doug Ford continues his celebration of our Island coastline

FROM the Nez de Guet, where Rozel Bay ends, to Vicard Point, where Bouley Bay ends, is about one and half miles as the crow flies.

Here the coastline is mainly backed by 200-300 ft cliffs.

Immediately to the west of the Nez de Guet is a small cove called Le Sauchet, which means ‘a place drenched with spray’.

The next headland is the Tour de Rozel with its widely recognised White Rock and tidal race, which has been the scene of a number of shipwrecks over the years.

Just beyond L’Etacquerel Fort lies the remains of the SS Ribberdale, which was wrecked on the night of 26 December 1926.

She was waiting to take on a cargo of granite from Ronez when she dragged her anchor during a gale and was driven ashore.

The captain and crew succeeded in reaching shore on a small boat, however one of the firemen was missing.

He turned up safe later in the day having ‘slept through the whole affair’.

In April 1887, the 30-ton coaster, Normandy, foundered here while running for shelter, the only survivor was the ship’s boy who was found the following morning clinging to the cutter’s upturned small boat.

The rough pasture on these cliffs was used in medieval times to graze the coarse-fleeced multi-horned sheep that were the foundation for the Island’s famed knitting industry; although Islanders very soon realised that more money was to be made by importing the better quality English wool for their product.

The popular notion of Bouley Bay is the area from L’Etacquerel to the pier.

L’Etacquerel comes from the old Norse word for a heap or a stack of rock – ‘stakkr’.

This can still be seen just below the 19th century fort.

The meaning of Bouley Bay, however, is a bit uncertain; one theory is that it comes from the old Norse words for a dwelling and a bay – ‘bol’ and ‘vik’.

As early as 1274 the area was referred to as the port of ‘Boley’ and in 1602 the States appointed Nicholas Richardson ‘superviseur pour les coustimes des Etats aux Harves de Rozel, Bouley Bay et Ste Catherine’.

However, the work was hardly onerous. Despite having long been recognised as the best deep-water anchorage in the Island the pier is of fairly recent construction.

In 1685 Philippe Dumaresq described the bay as ‘ . . . a very good road for any ships about two cables length (370 metres) from the shore, in 12 or 15 fathom water; secure for all southerly and westerly winds . . . indeed the fittest place for a harbour of all the island’ although he did qualify it by pointing out that the high cliffs behind it make building and access extremely difficult.

An invasion repulsed

This was also a lesson learned by the French in the summer of 1549 when they tried to mount an attack on the Island by landing here.

This was actually a diversionary attack designed to draw English resources away from their main campaign in Scotland.

The French sent two squadrons of galleys to attack the Channel Islands – an attack on Guernsey was defeated but they did successfully manage to capture Sark before moving on to Jersey.

An English naval force led by William Wynter defeated the French galleys while the French transports landed soldiers and Italian mercenaries in Bouley Bay.

Once assembled Captain Breuil (de Bretagne) led his men up the steep hill to Jardin d’Olivet where they were surprised by the Island Militia armed with their new cannon. Despite being totally defeated the French managed to get back to their ships and retreat to St Malo.

Two hundred years later the bay saw the arrival of another military force.

This time it was Lieutenant Colonel Rudolph Bentinck and four companies – about 200 men – of the Royal Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots).

They had been sent to Jersey to restore order after the anti-Lemprière riots in September 1769.

This time there was no armed resistance, which is just as well, as by then there were a number of defensive structures around the bay to prevent any such hostile landings.

The seas bounty

Before there was a pier several large fishing boats were kept here.

They were usually hauled above the high-water mark using Crabbs (Capstans).

When the oyster industry was expanding in the 1820s it was decided to build a pier here and so Abraham de la Mare was commissioned to do the job.

His pier, finished in 1827, was 36 metres long and nearly 14 metres high and completed at a cost of £2,500.

It was designed to provide shelter for up to 30 oyster cutters.

Six of them were actually built here between 1824 and 1842.

The Blampieds built four of them although the largest – a 40-ton cutter – was built by John Pope in 1826.

Over the same period another six open boats were decked over by the Le Masuriers.

Today Bouley Bay is popular with scuba divers and snorkelers.

Its sheltered water is home to a wide variety of marine life and in 1993 the States’ landing barge, La Mauve, was scuttled about half a mile offshore to create an artificial reef for the enjoyment of recreational divers.

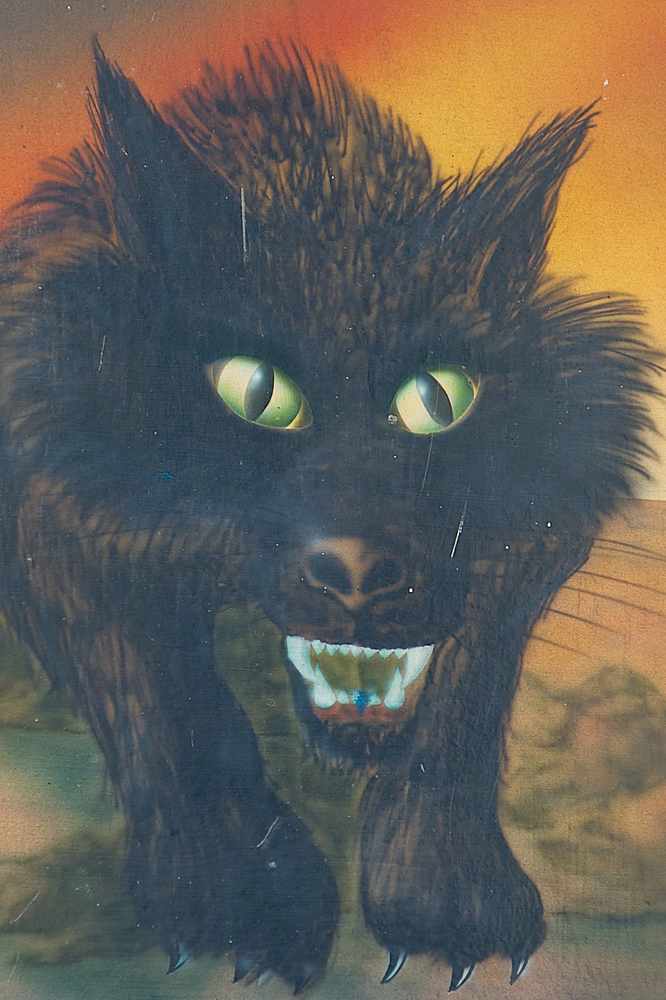

The black dog

The bay is also associated with a couple of myths.

The best known is that of a gigantic black dog with huge saucer-shaped eyes – le Chien de Bouley (le Tchan du Bouole) – which is said to roam around the area frightening innocent passers-by.

This may have been a story circulated by smugglers to keep prying eyes and gossips away from the bay and possible clandestine activity.

The older story associated with the area is the Cry of the Tombelènes with its local lovers, an army of occupation, murders and suicide set around the cliffs (Les Tombelènes) above the Islet during the French Occupation of 1461 until 1468.

Beyond the pier the cliffs continue to Vicard Point, which takes its name from the old Norse Vik-vartha – the watch hill by the creek.

It doesn’t look much today, but in the late 17th century this little creek was referred to as Havre Vicart and described thus: ‘Here boats might land passengers but they can only ascend the cliffs in single file’.

Sea travellers back then were obviously a hardier bunch.