Kat Tiefenthal describes how her family, who travelled from Jersey to Svalbard, enjoyed last week’s cosmic wonder from their own home.

HOW often do you get to see a total solar eclipse without moving from your armchair?

We found out a year ago that the little cabin that we inherited in the remote Arctic lies under the path of the 2015 total eclipse – and quickly booked our flights.

We got the last seats. All the accommodation had already sold out. The local population of 2,000 was predicted to more than double. I worried that the little mining settlement would be unable to cope, and whether the 3,000 polar bears would stay away, and whether it would be cloudy. According to records, there would be only a 16% chance of clear skies.

My Norwegian husband and I have seen a total eclipse before, in Transylvania in 1999, when I was pregnant with our twins. Now they are 15 and keen to see what all the fuss is about.

This eclipse is special: not only does the moon pass its closest point to the earth in its orbit, and it coincides with the spring equinox, but in the archipelago of Svalbard, half-way between Norway and the North Pole, they get super-excited about the sun. By the time of the eclipse, they will have just emerged from four months of total darkness.

As soon as we arrived at 78 degrees north, we were absorbed into the debate about the best place to watch the phenomenon. Most tourists would see it from the wide open fjord just outside town, but if you had access to some skis or a snowmobile, the choice was yours.

My husband, being a true local – one of only 50 people ever to have been born on Svalbard (the first was his uncle in 1919) – knew all the best spots, all of them at the top of mountains. I worried about getting there in one piece. Snowmobiling up vertical slopes is not for the faint-hearted. And I worried about freezing to death or losing a few toes. It’s minus 28 and the wind is howling.

Partial eclipses happen when the moon comes between the sun and the earth, but they don’t align in a perfectly straight line.

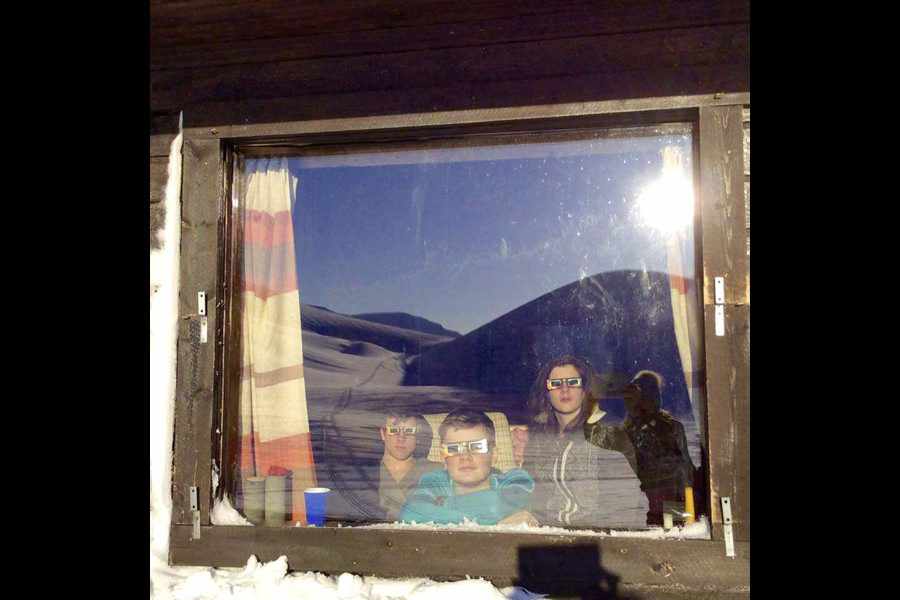

Fortunately, my husband worked out that we would be able to see the eclipse from the comfort and warmth of our little cabin, far away from anyone. Norwegians like their personal space. Although it’s nestled in a bowl, there is a gap between two hills just wide enough to allow the passage of the sun from 10 am to midday. What luck – totality is due at 11.11 local time!

The day finally arrives. It’s a beautiful morning, wind-still and silent: nothing but dazzling white snow outside the window. It stings my eyes, even though we are still in the shade.

It’s very cold but I have to go outside to fill a pot with snow to heat on the paraffin stove to make coffee. I see the fresh prints of an Arctic fox around the cabin and I startle a fluffy white ptarmigan into the air. It has no clue that today is a special day.

The rest of the family are still sleeping. Only the smell of sizzling bacon arouses them from their warm duvets. I hope it doesn’t draw a polar bear inland from the coast, but our rifle is loaded, leaning against the back of the sofa, just in case.

There is a tingling thrill in the air. In an hour’s time we will witness the cosmic wonder which must have terrified ancient civilisations. We know that the darkness will last just two and half minutes, and that the sun, the source of all life, will return. The wildlife up here do not know that.

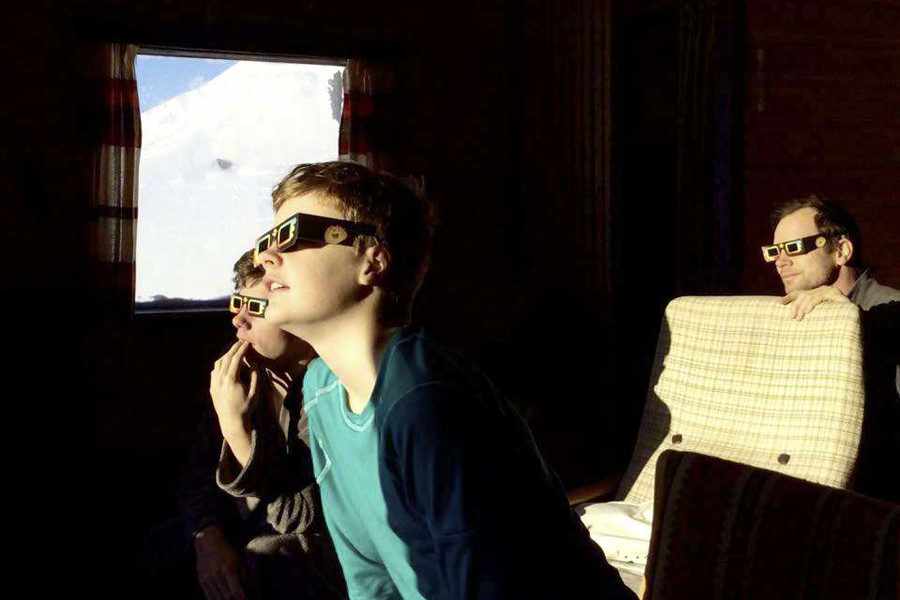

It’s nearly P1, the first stage of a partial eclipse. We don our glasses and wait for a bite to appear in the right-hand side of the sun as we tuck into our breakfast.

There is not a cloud in the sky. There are rumours that we will see stars and comets and passing satellites and meteors and even the Northern Lights. The excitement grows as U1, the moment of total eclipse, approaches.

I am suddenly worried about safety and warn the kids not to look at the sun without the glasses. My eldest son has stuck a photo film to the window and lined it up with the rocking chair so he doesn’t have to use the glasses. They look naff, apparently. He points out that when the moon covers the sun completely, we can look with the naked eye with no fear of going blind.

My youngest son is lying in bed in a bright shaft of light with his glasses on. He thinks it’s super sick that he can stare at the sun, eyeball to eyeball. He’s winding me up. I check our glasses for scratches, just £2 from Amazon, but they seem to be OK.

The sun radiates intense ultra-violet and infra-red radiation in addition to visible light that could blind in just a few seconds.

We watch as the moon continues to devour the sun, bit by bit. The lunar shadow moves slowly towards us across the valley. It starts to get murky (which is a Norwegian word meaning ‘dark’ I learn from my husband.)

I imagine that the reindeer I saw further down the valley are getting sleepy and getting ready for their shortest night ever. During the 1999 eclipse I remember the cows around us settling down in the meadow.

In the final countdown to U1, the kids are getting increasingly frisky. The thumbnail sliver of sun is disappearing fast. I hear my eldest son saying that we can already look at the sun with the naked eye. Really? I say. ‘Yeah! It’s so cool!’

Stupidly, I take off my glasses and am temporarily blinded by a bright flash of light just as the moon slots over the sun and the bright silver halo snaps into view and everyone goes mad, whooping and screaming. We are plunged into the moon’s shadow. The sky turns instantly to a deep indigo. Eerie. Ripples appear in the snow and intensify all around us like sunlight playing on the surface of the water. I look across the sky and see several bright dots, daytime stars, then many more dots as I turn back to the dark side of the moon.

‘Wow, look at the corona!’ someone shouts.

I look but see only flashes of green and purple jiggling right over the moon.

‘Look at Bailey’s Beads!’ says my husband from his armchair. ‘That’s sunshine cutting through the valleys on the moon’s surface and prominences! Look at the streamers shooting out of the corona! Amazing!’ It’s rare for a Northerner to expel so much enthusiasm.

- The next total solar eclipse on Earth will be on 8/9 March 2016, across South-East Asia, North East Australia and the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

- After that, total eclipses will take place in 2017, 2019 and 2020, covering areas of North and South America and the South Western fringe of Africa.

- The next total eclipse visible from mainland-UK will be in 2090.

We move outside. It’s freezing. We’ve not had time to dress properly. We stand in a row in front of our little cabin, the five of us with our funky cardboard glasses on.

My daughter thinks the bursts of flame around the halo look like the sparkly petals of a beautiful golden flower. My eldest son draws our attention to the rainbows of fire surrounding the ring of white light, and notices how dark the ball of the moon is inside.

I can see none of these things, just the colourful splodges which I assume are the Northern Lights, dancing before my eyes. I wonder why no one else can see them.

After 147 seconds, we move into the U2 phase as the moon carries on its path and moves off the sun, creating a small burst of light on one side.

‘A diamond ring!’ I hear my daughter scream. ‘Where?’ I scream back. ‘Wow. Amazing Northern Lights!’ I exclaim, ‘right on the moon!’

The sun returns. We have moved into P2. It’s all over.

‘What Northern Lights?’ My husband assures me that what I saw were not Northern Lights. In the 20 years he lived up here, he saw them regularly during the polar winters, but they were rarely colourful. This far north, they are nearly always milky-white.

The kids chatter and bubble, exchanging the highlights of the experience with ever increasing superlatives. My eldest says the coolest thing was being able to look right at the sun with no glasses, that this was the only time you could stare right in the face of danger. I suddenly realise that I had been temporarily blinded by removing my glasses too early and had missed the whole thing.

‘Never mind, Mum, the next one in Europe is in 2081,’ the kids inform me – now fully qualified umbraphiles!